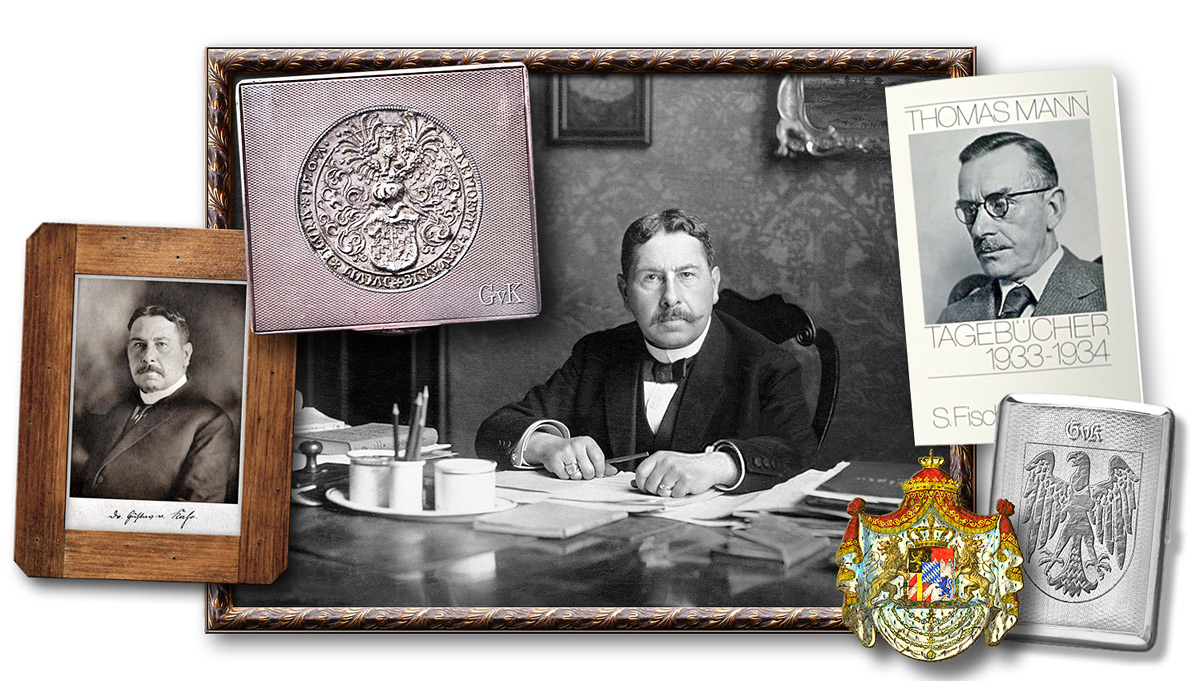

VII. Jane Turner Rylands’ Betrug an Olga Rudge

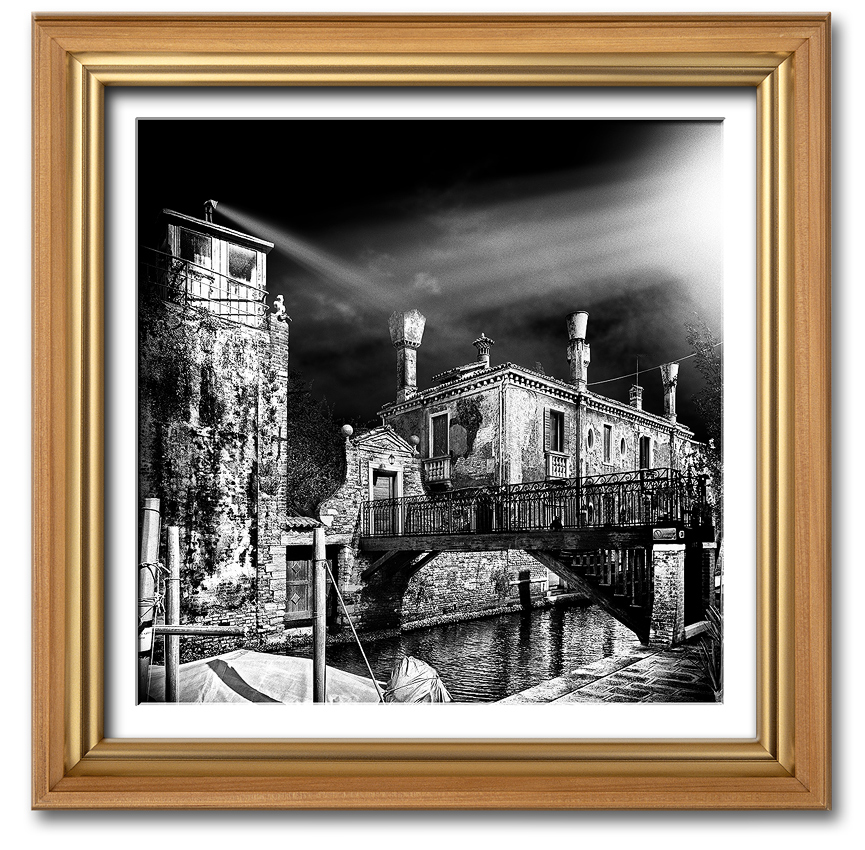

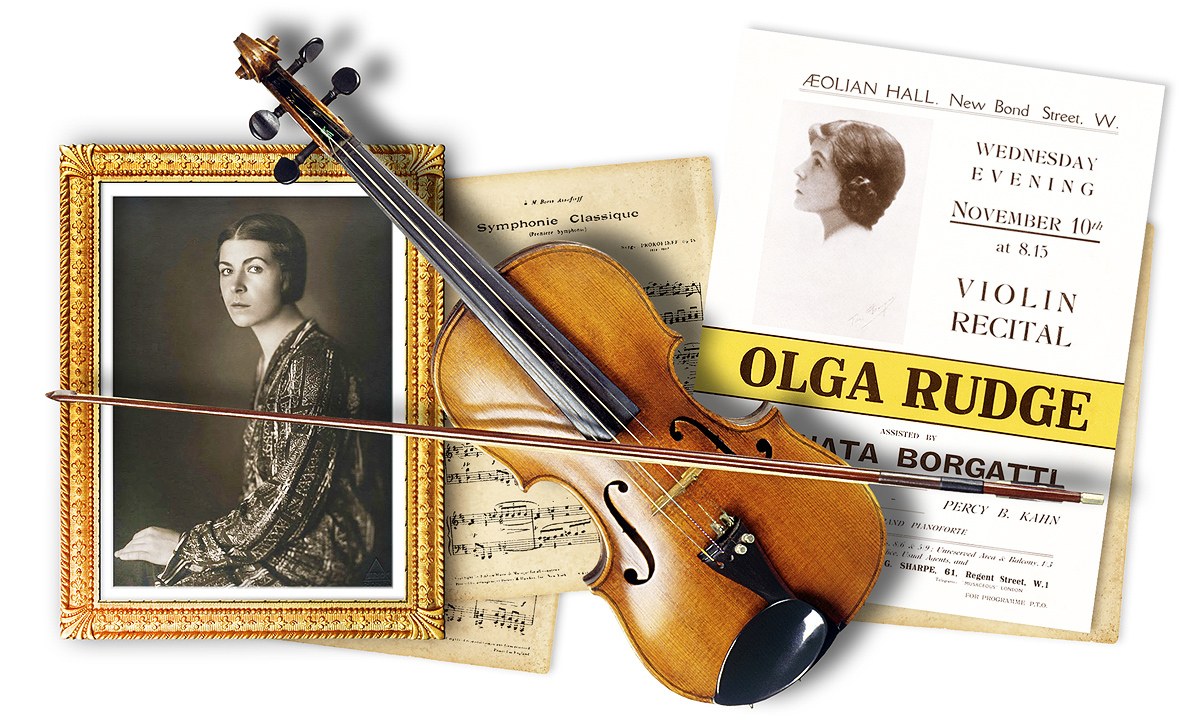

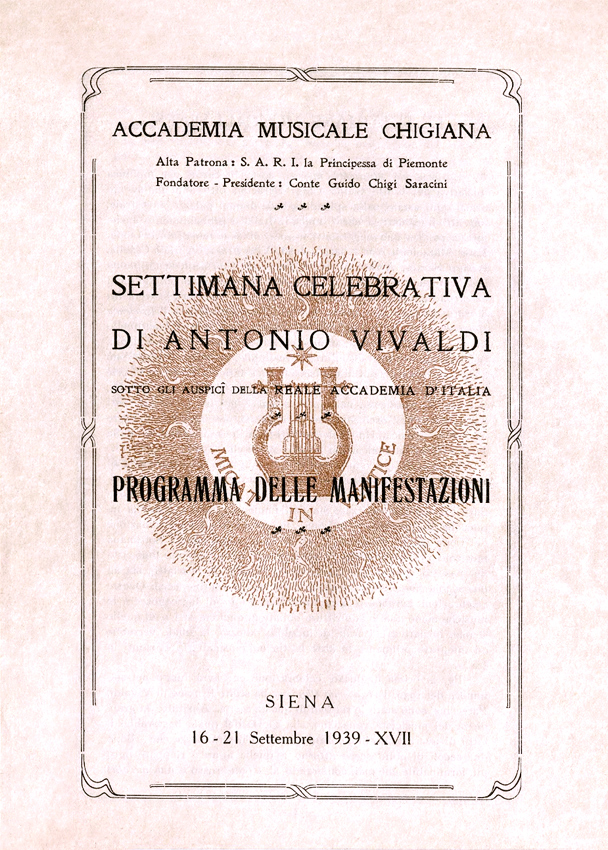

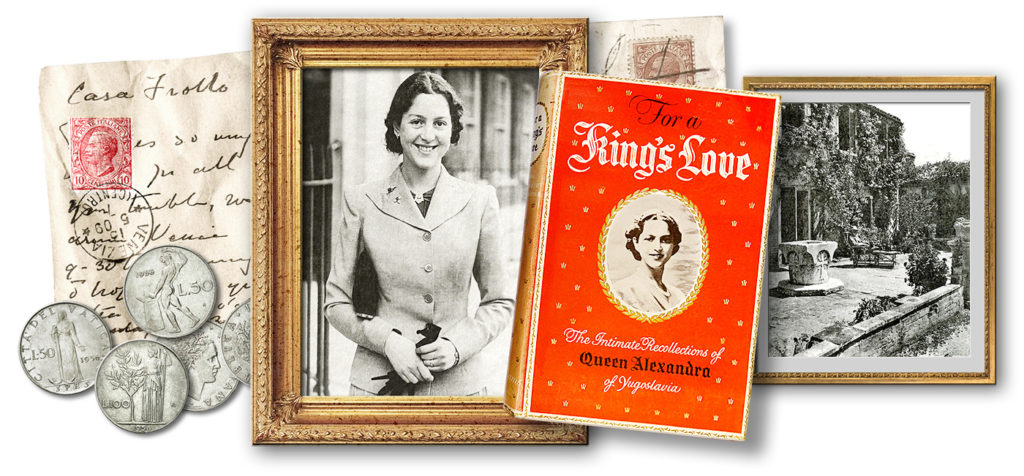

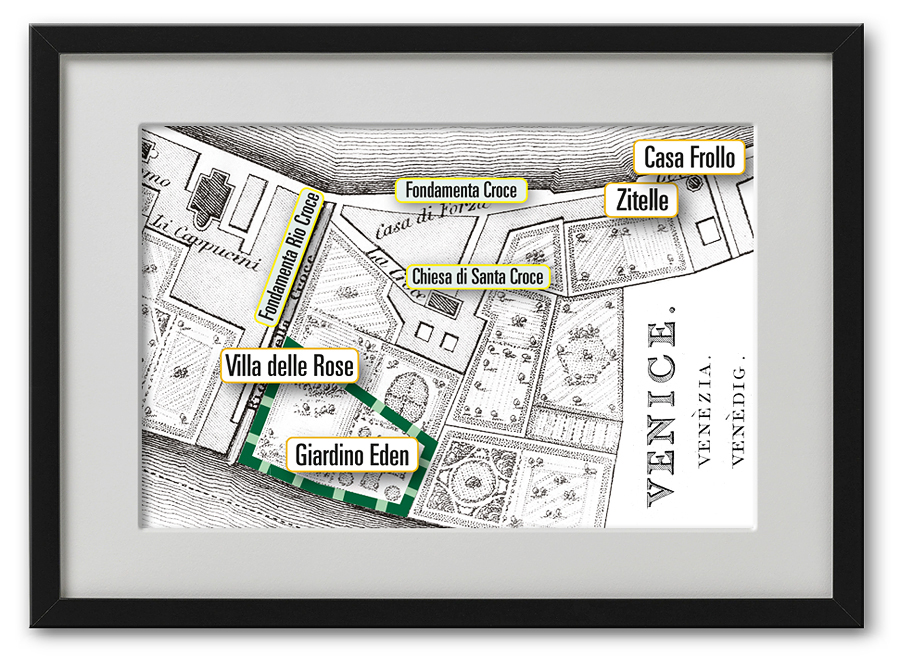

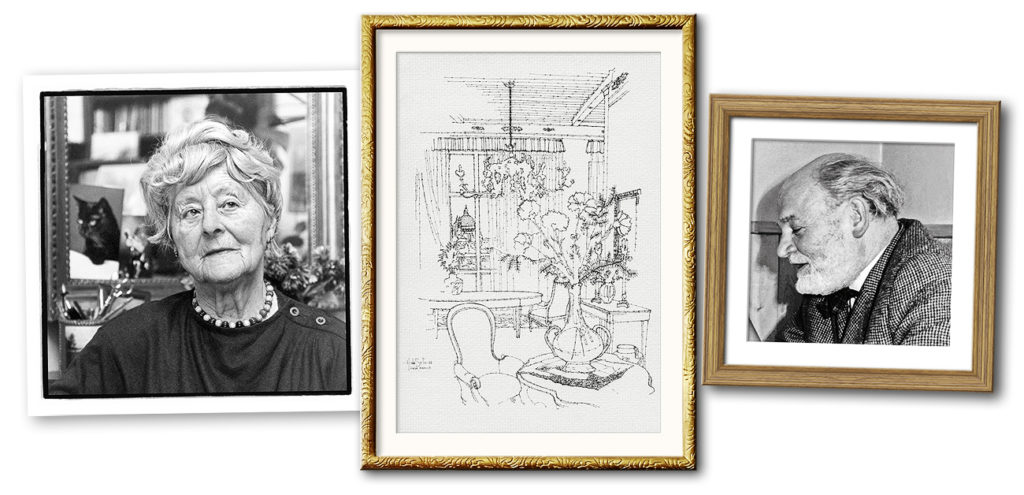

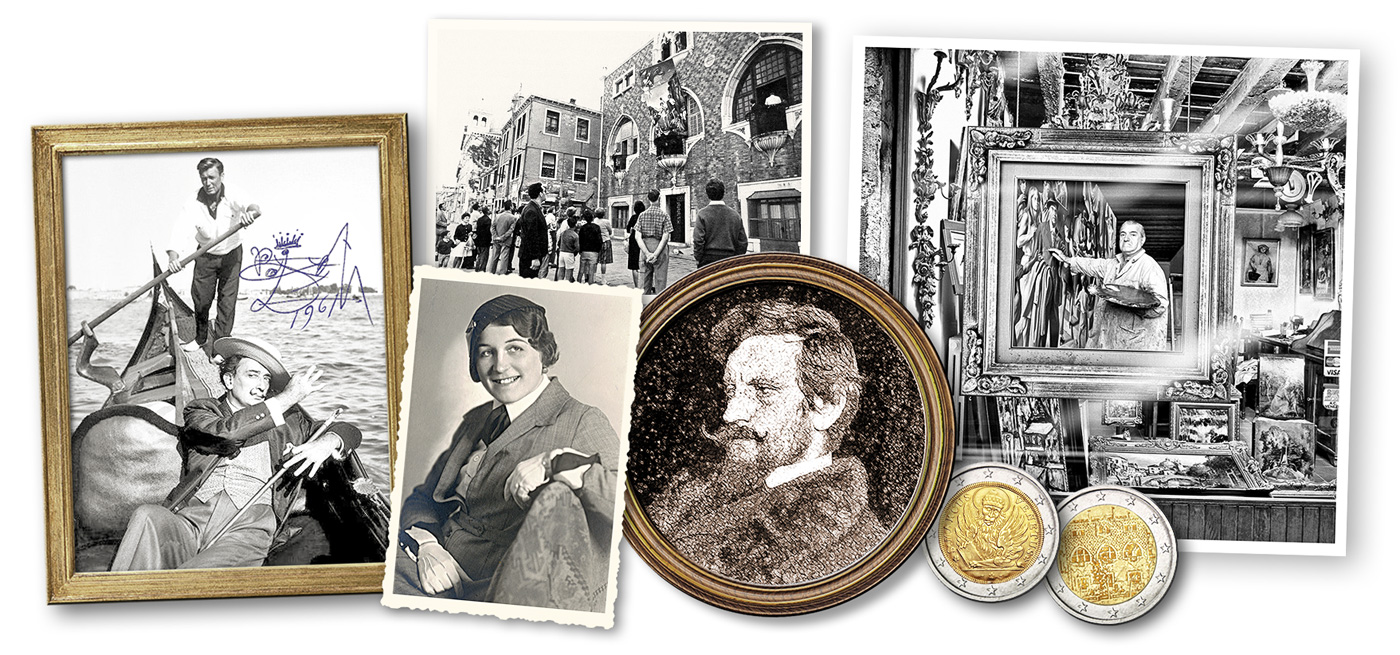

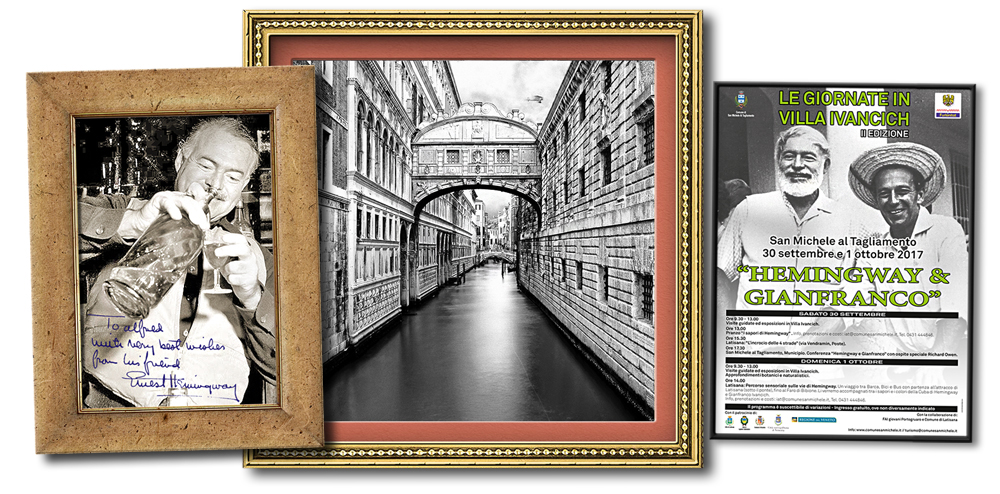

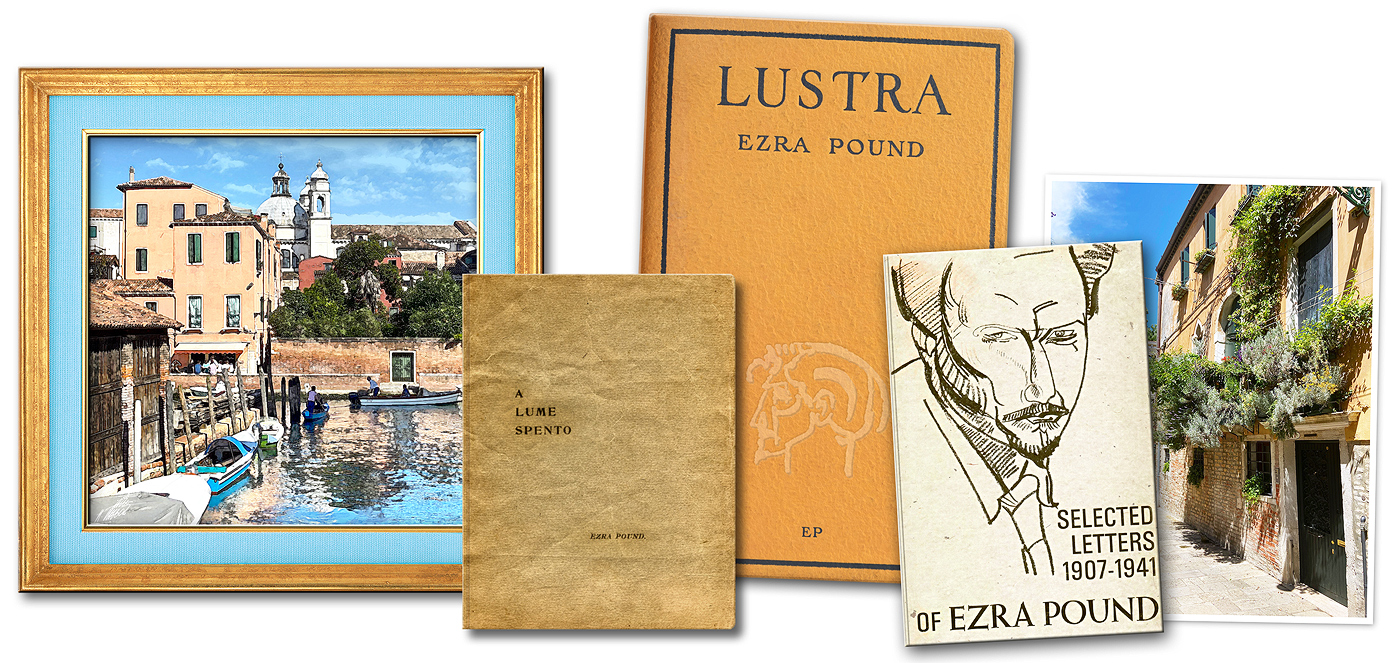

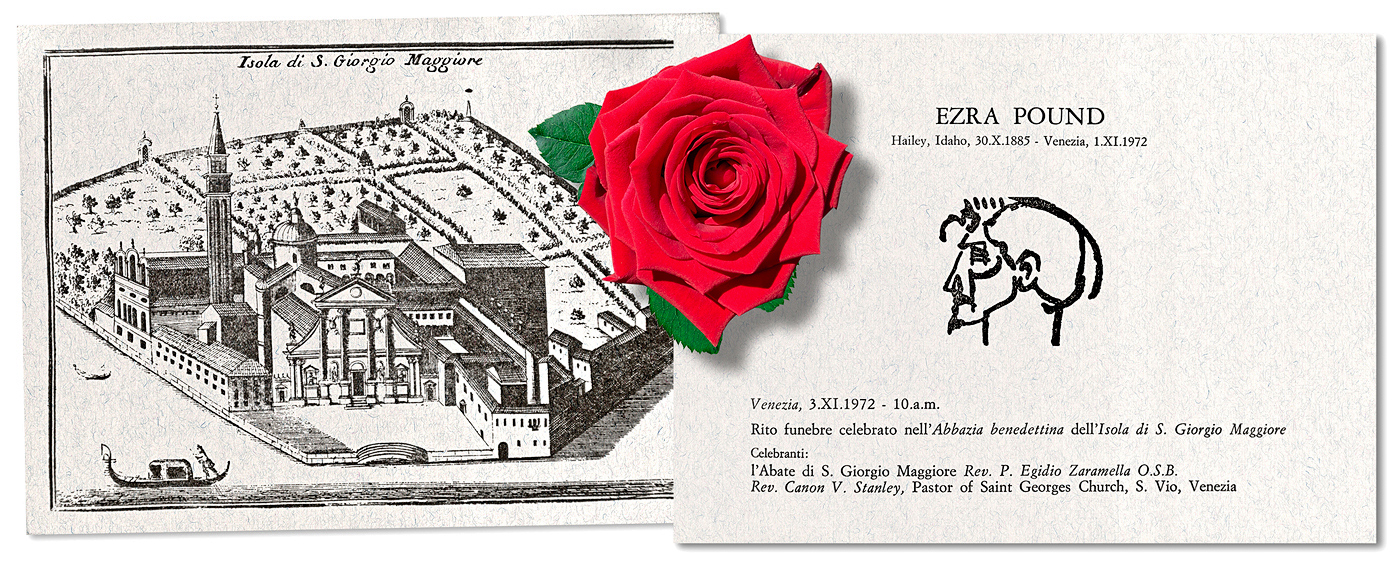

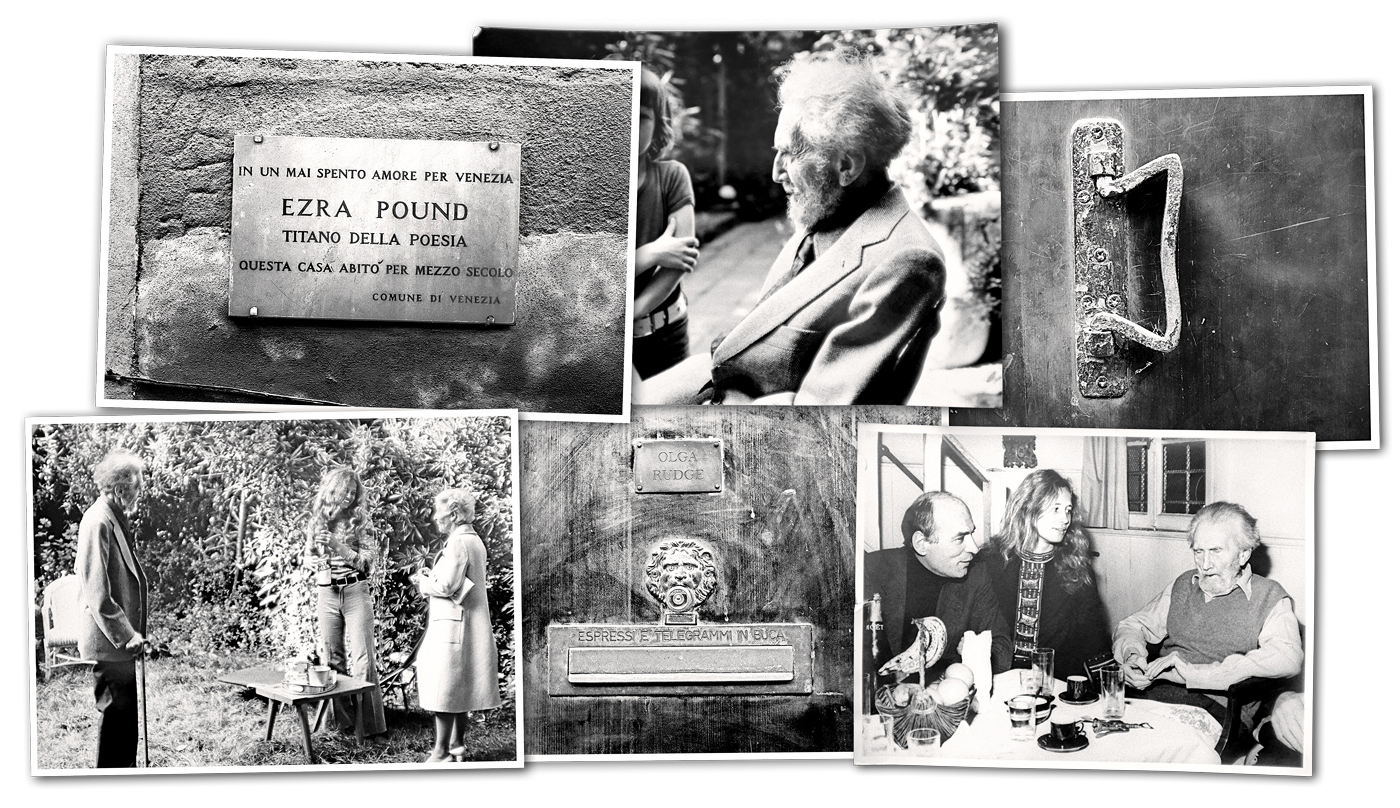

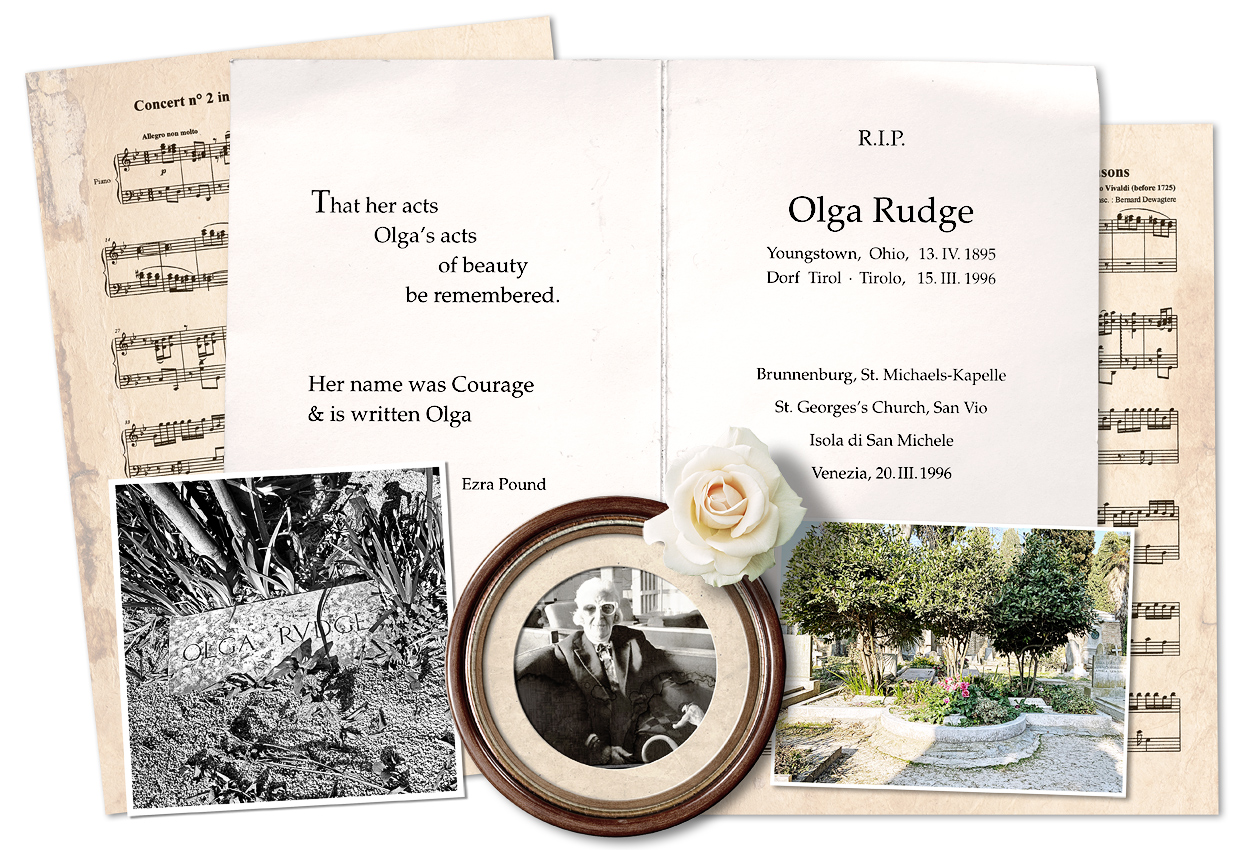

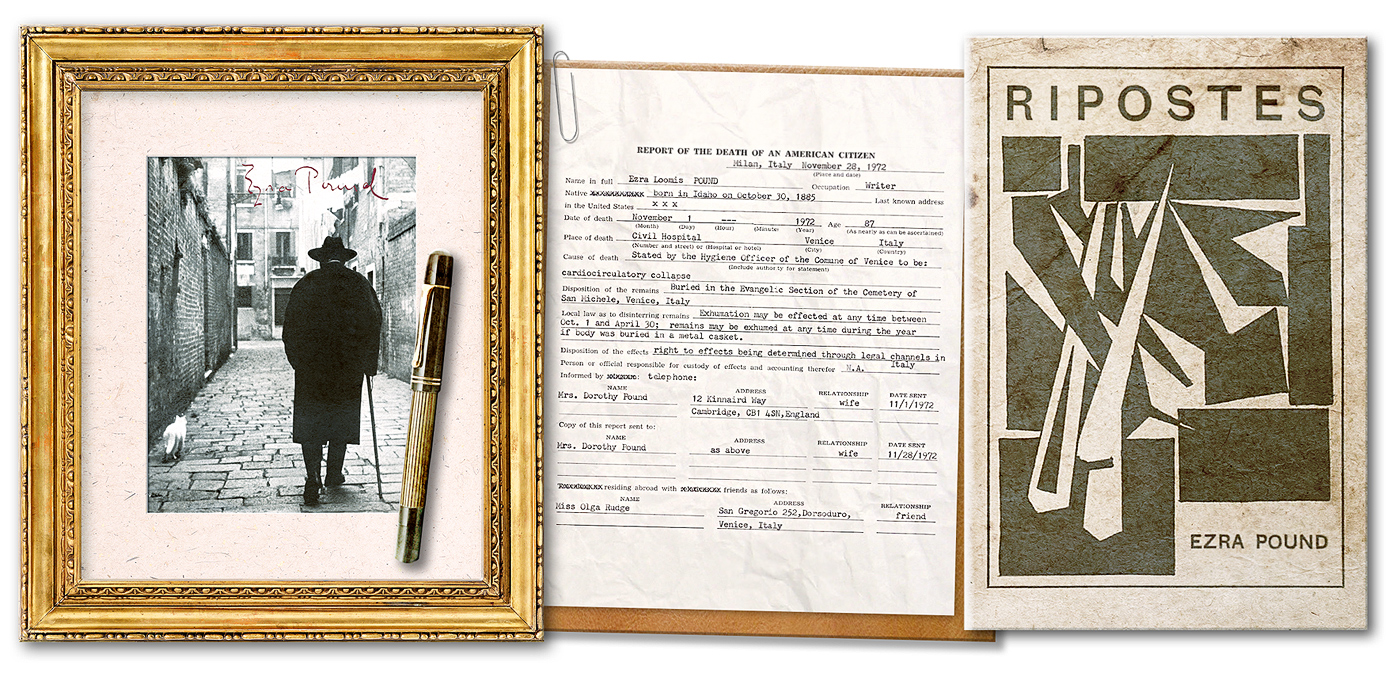

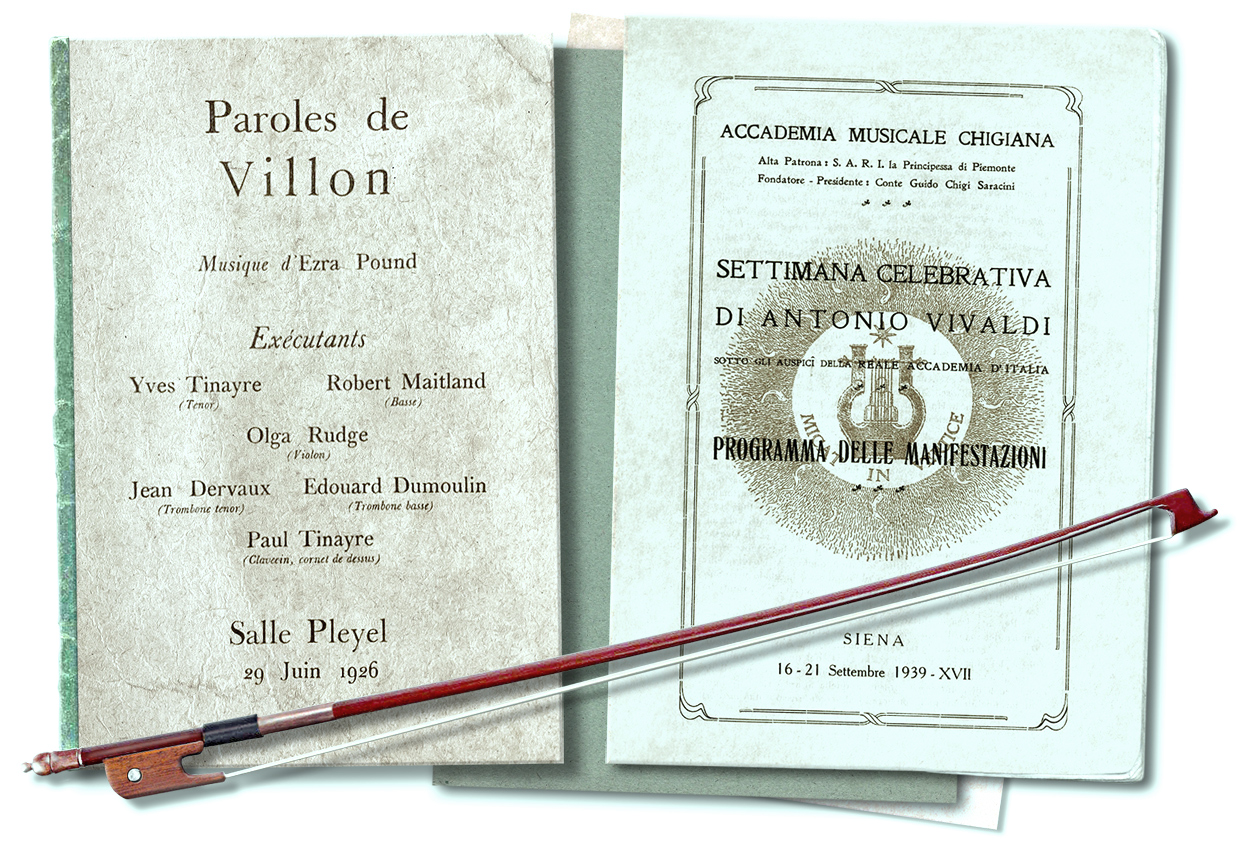

Olga Rudge, US-amerikanische Geigerin, Gründerin des Centro di Studi Vivaldiani an der Accademia Musicale Chigiana war im 78. Lebensjahr, als ihr Lebenspartner Ezra Pound in Venedig verstarb. (Siehe meinen Blog vom 5. Oktober 2020: Ombra e luce – musica veneziana della notte.) Im venezianischen Kulturgeschehen war sie auch nach seinem Tod sehr aktiv, hatte in vielen künstlerischen Organisationen ein gewichtiges Wort mitzureden und richtete Galaabende und Charityveranstaltungen aus. „Over the next decade Rudge continued to have contact with Pound scholars; she helped organize several exhibits and tributes to Pound and pursued several possible plans for memorials in Idaho and Venice.“ 1)

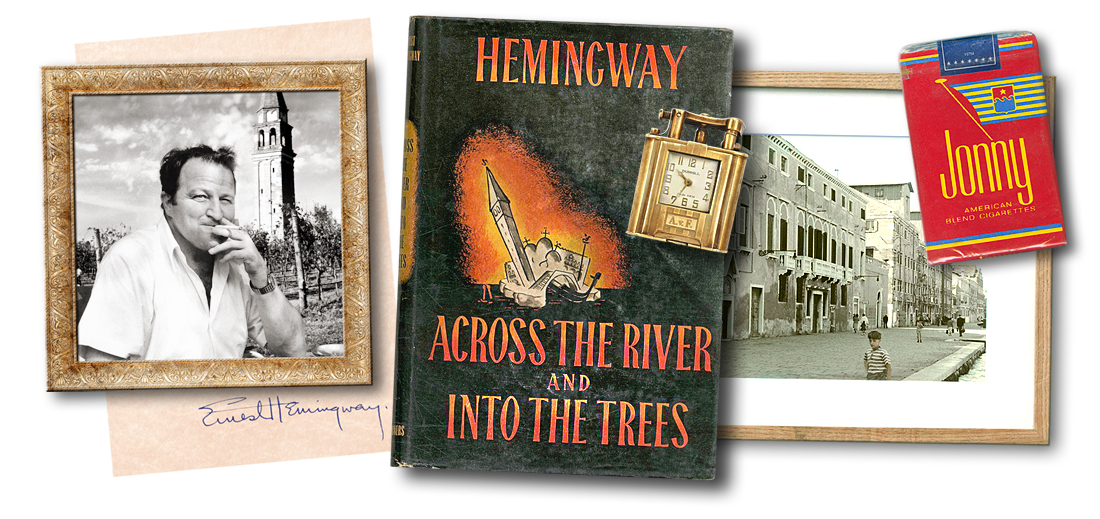

In der oberen Etage des Hauses am Rio Fornace nahe der Salute-Kirche, das sie mit Ezra Pound geteilt hatte, beherbergte sie viele aufstrebende, junge Literaten und bildende Künstler und nahm als Aufwandsentschädigung höchstens kleine Gemälde und dedizierte Gedichte an. Ein großes Anliegen war ihr stets, Pounds Arbeit zu fördern und seinen Ruf gegen den Vorwurf des Antisemitismus und Faschismus zu verteidigen, der ihn sein halbes Leben begleitete. 1967 wirkte sogar Pier Paolo Pasolini maßgeblich an dem von der RAI produzierten Dokumentarfilm Un’ora con Ezra Pound mit, worin der kommunistische Regisseur und Dichter seine Bewunderung für Pound kundtat und seine Gedichte in italienischer Übersetzung rezitierte.

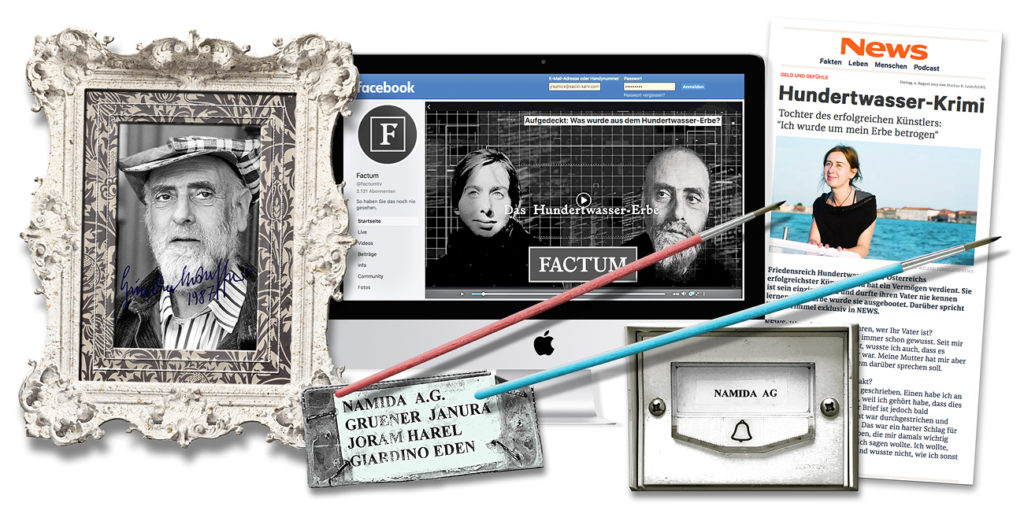

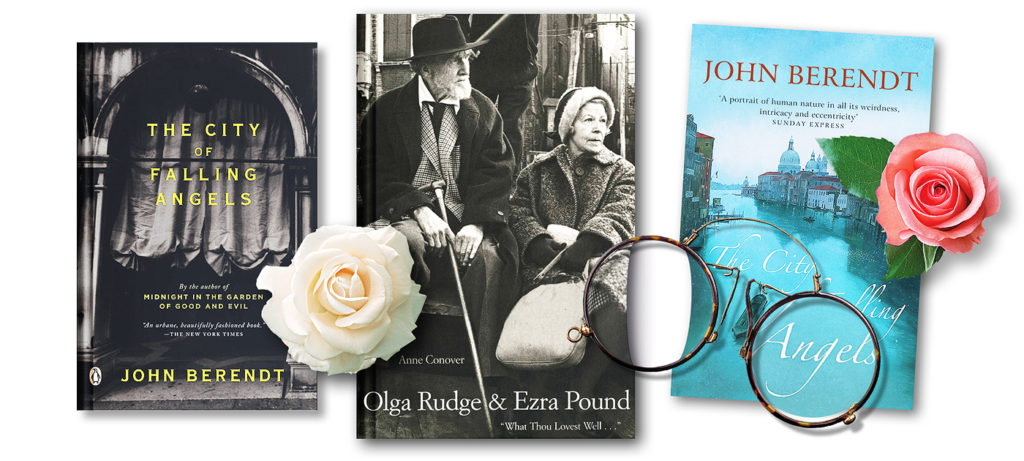

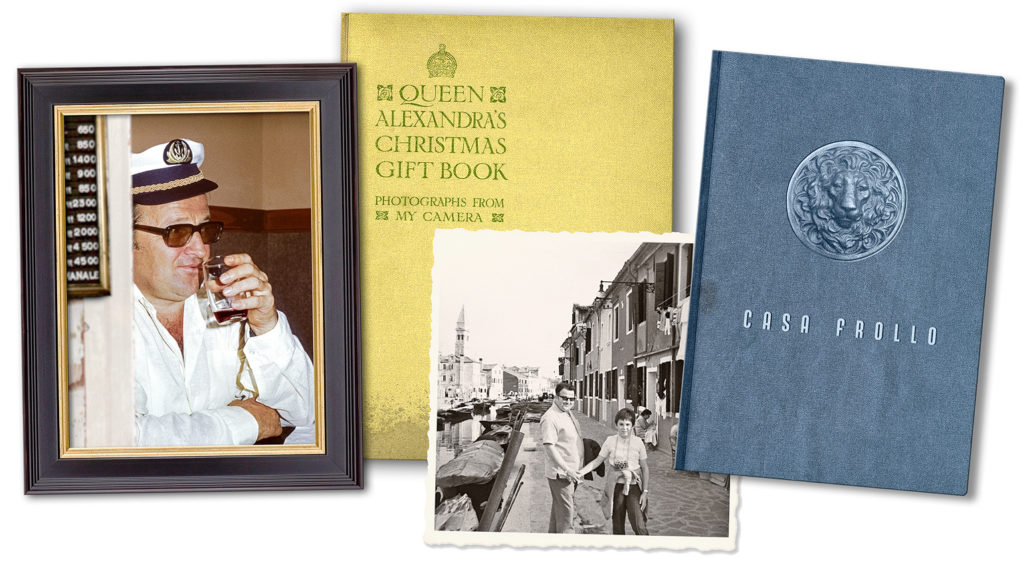

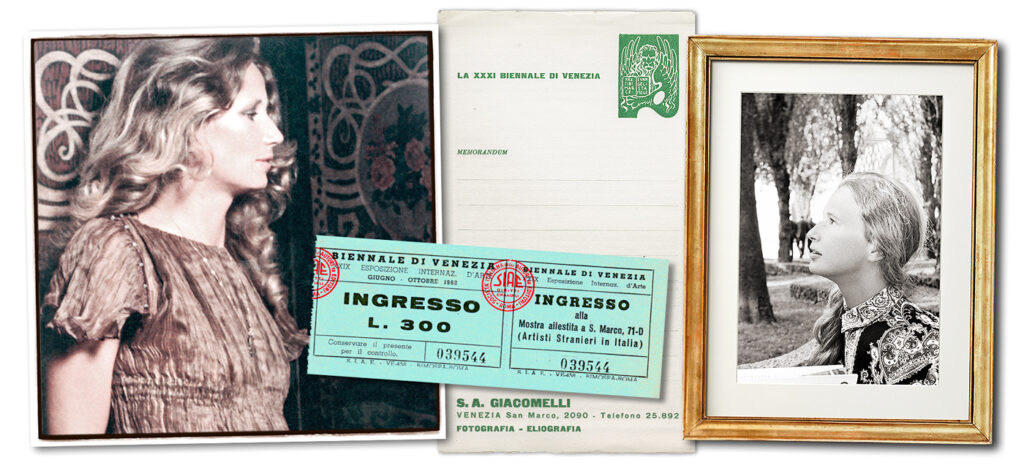

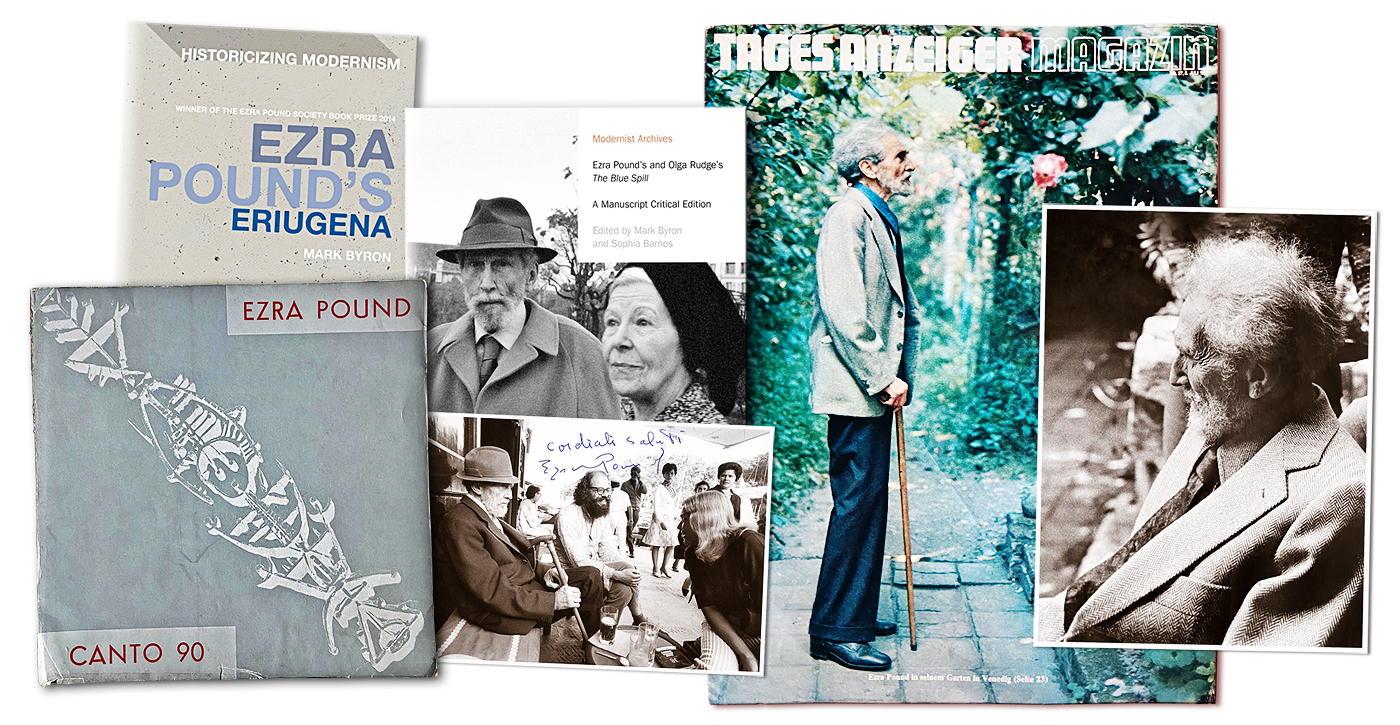

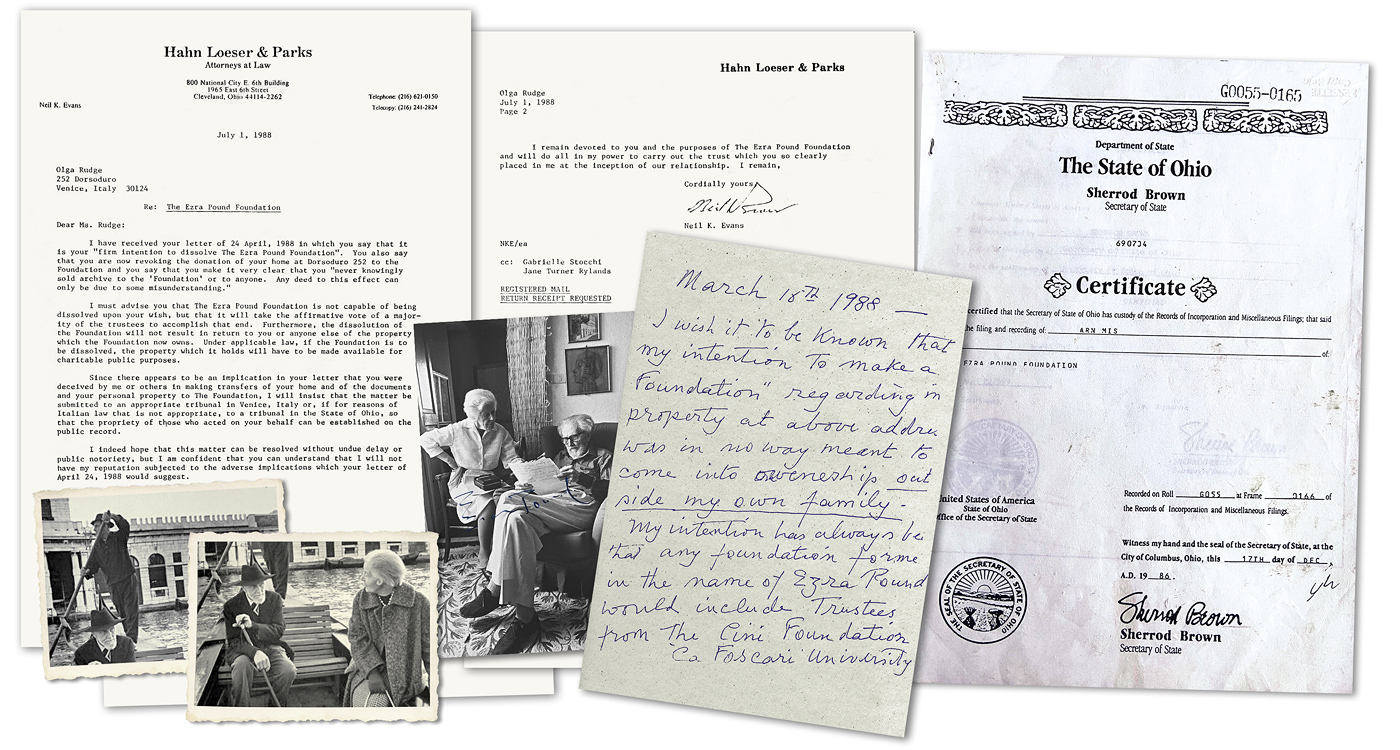

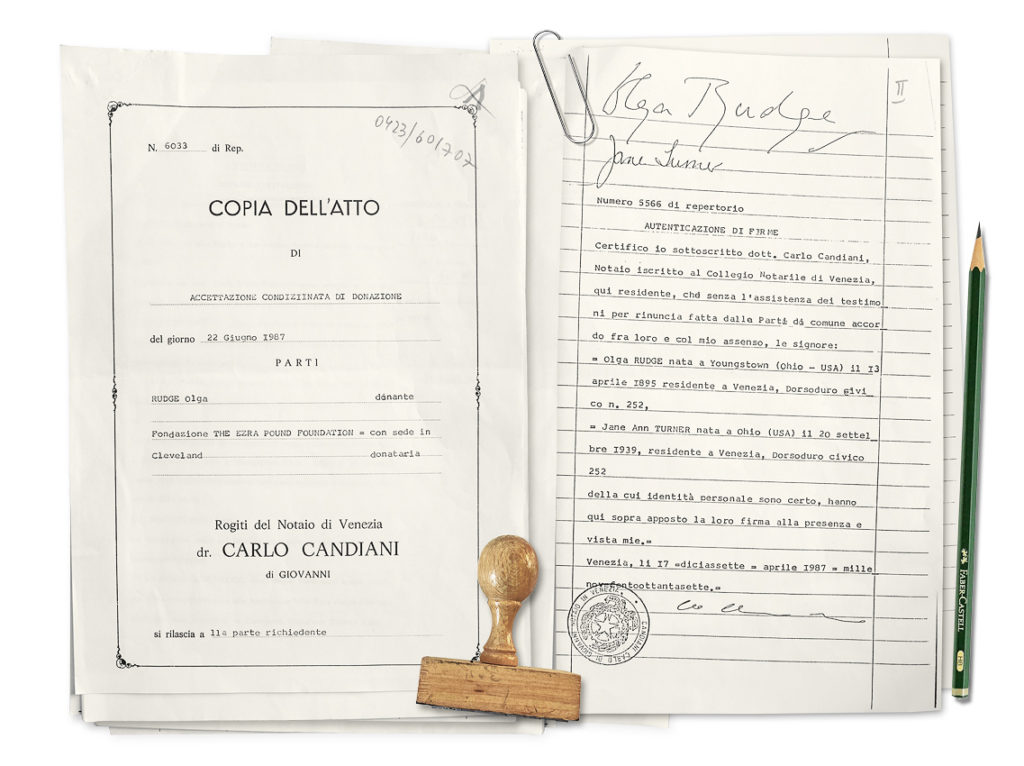

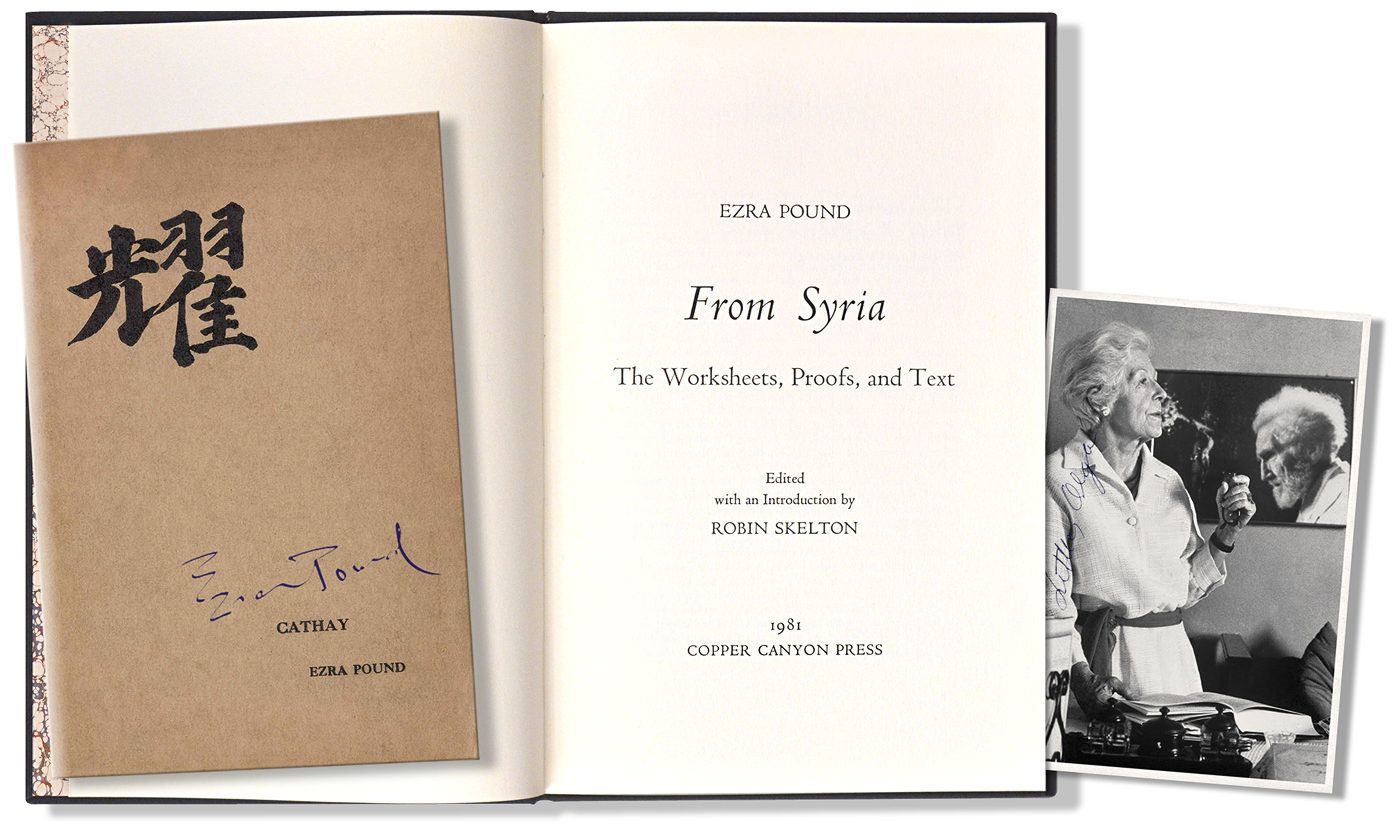

Nach dem Tod ihres Partners war es Olga Rudges vordringliche Absicht, eine Stiftung ins Leben zu rufen, die Pounds Gesamtwerk fördern und die Forschungsarbeit daran vorantreiben sollte. Im Jahr 1986 drängten eine amerikanische Freundin Olgas, Jane Turner Rylands, und ein Anwalt aus Cleveland, Ohio, Olga Rudge, mit ihnen die „Ezra Pound Foundation“ zu gründen. Wiederholt wurde Olga von vielen Freunden gewarnt, Papiere zu unterschreiben, die von Rylands vorgelegt wurden. Schon im Vorfeld der Gespräche verschwanden Truhen aus Olgas Haus, in denen unersetzliche Papiere von Pound lagerten, darunter literarische Schriften und Manuskripte, Tagebücher, die gesamte Korrespondenz, Zeitungsausschnitte, Bücher und Alben mit Skizzen und Zeichnungen, Tonbänder, Kompaktkassetten und anderes dokumentarisches Material. Der amerikanische Journalist und Schriftsteller John Berendt recherchierte vor Ort und beschreibt diesen Skandal in seinem Buch Die Stadt der fallenden Engel im Kapitel Der letzte Canto: „… einmal, zur Weihnachtszeit, entfernte Jane (Rylands) die Truhen, um Platz für Olga zu schaffen, wie sie behauptete, und die Papiere vor Hochwasser in Sicherheit zu bringen. Entweder hatte Olga es vergessen, wo Jane sie hingetan hatte, oder Jane hatte es ihr nicht erzählt. Jedenfalls machte sich Olga bald darauf Sorgen um die Papiere und beschwerte sich bei mehreren Leuten, dass Jane ihre Truhen fortgeschafft habe und dass sie, Olga, nicht wisse wohin. Schließlich bat sie Jane, sie ihr zurückzubringen, was diese auch tat. Doch Olga zufolge waren sie leer, als sie sie öffnete.“ Der legendäre und einzigartige Arrigo Cipriani rettete sozusagen die Papiere und sprach im Interview mit Berendt von einer „hässlichen Geschichte“. Jane Rylands bat Cipriani nämlich um einen Lagerplatz in seinem magazzino, da sie gerade Olgas Wohnung reinige und Platz für einige Dinge bräuchte. Nachdem Cipriani erfuhr, dass folglich Jane Rylands neuerdings in seinem Lager ein- und ausginge, hielt er Nachsicht und entdeckte in seinem eigenen Lager „große Stapel von Papieren, die in Klarsichtfolie eingewickelt waren. Sie waren beschriftet, nicht berühren stand da drauf, Eigentum der Ezra Pound Stiftung.“ 2)

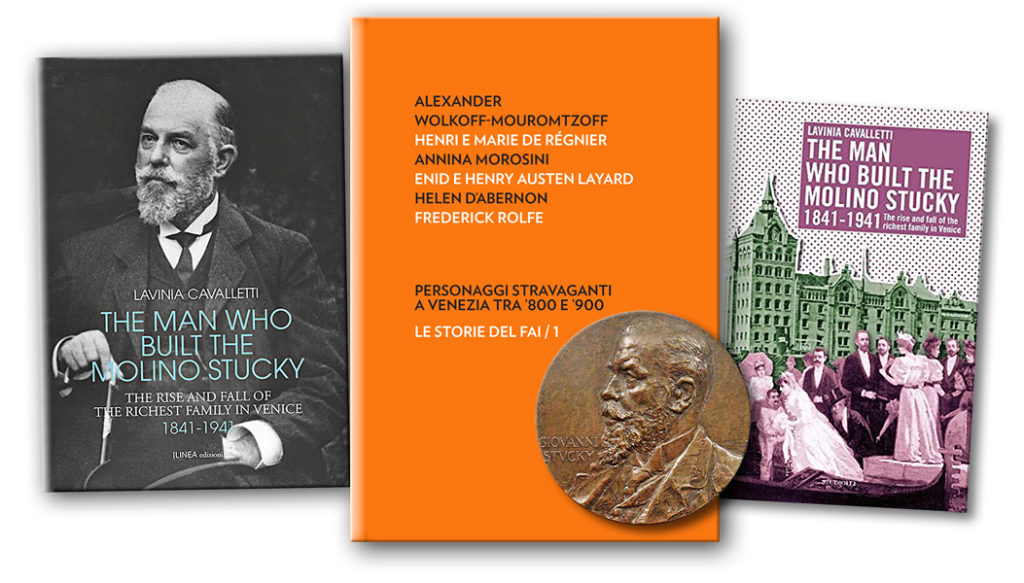

Unter mysteriösen Umständen verkaufte Olga Rudge in scheinbar verwirrtem geistigen Zustand 3) im 91. Lebensjahr den größten Teil ihres Archivs und ihr Haus an die Stiftung für eine lächerliche Summe von etwa siebentausend Dollar, was niemals von Seiten der Käufer nachgewiesen wurde. Ein Dokument existiert – ein leerer Bogen Papier, auf dem sich Olga Rudges Signatur an der Oberseite befindet. Darunter, sicherlich erst zu einem späteren Zeitpunkt eingefügt, ist der Text des Kaufvertrags. Nach dem Skandal, der auf die Stiftungsgründung folgte, reklamierte Rudges Familie, dass ein Verkauf niemals beabsichtigt gewesen sei, und dass Immobilie und Archiv ja um ein Vielfaches mehr Wert seien. „There is the imbroglio over the Ezra Pound collection. Olga Rudge, Pound’s elderly widow, sold 208 boxes of his materials worth well over $1 million for just $7,000. They went to the Ezra Pound Foundation, controlled by Rudge’s friend, Jane Rylands, whose husband is the director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. When Rudge tried to get access to her husband’s material, she was refused.“ 4) Im April 1988 schrieb Rudge an den Anwalt in Cleveland und informierte ihn darüber, dass sie die Stiftung auflösen wolle. Er antwortete ihr, dass ein solcher Antrag nicht im Rahmen des Gesetzes vorgesehen sei. Die betreffenden Papiere wurden in der Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, hinterlegt, wo sie bis heute untergebracht sind, und die Ezra Pound Stiftung wurde aufgelöst. Eine Box mit Papieren, die die Übertragung des Archivs aus der Ezra Pound Stiftung belegt, kann nicht öffentlich eingesehen werden – falls diese überhaupt jemals existiert hat.

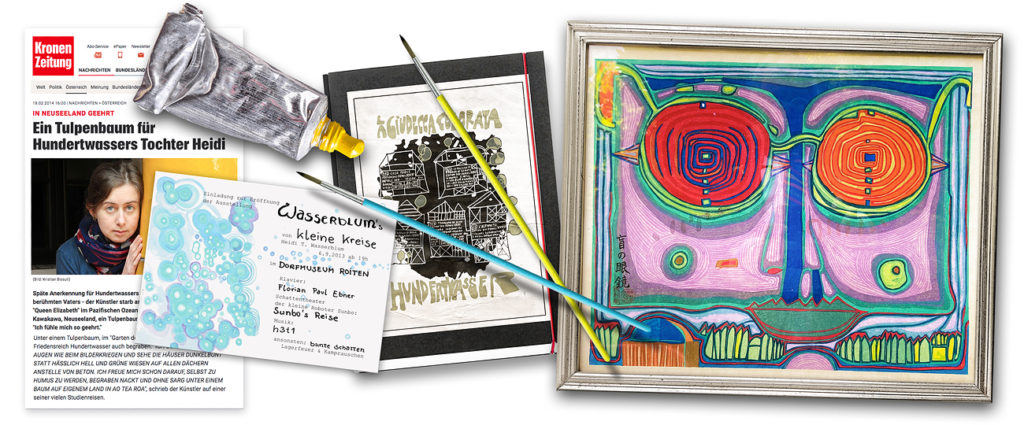

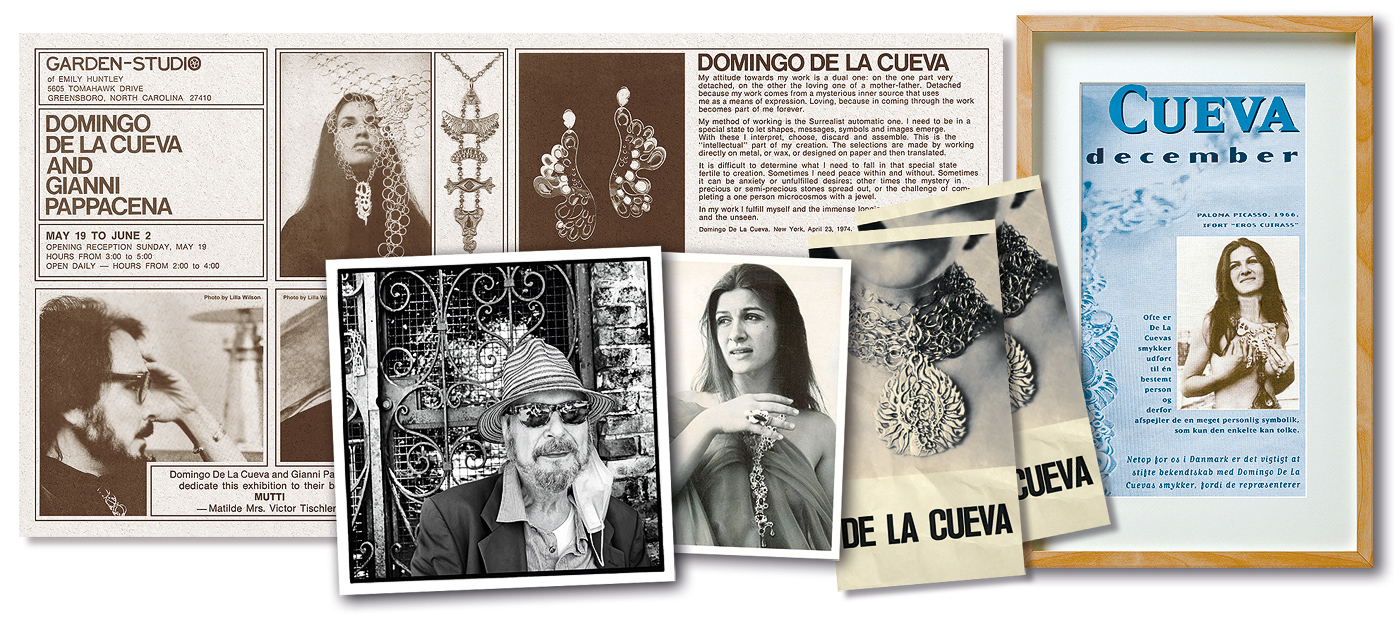

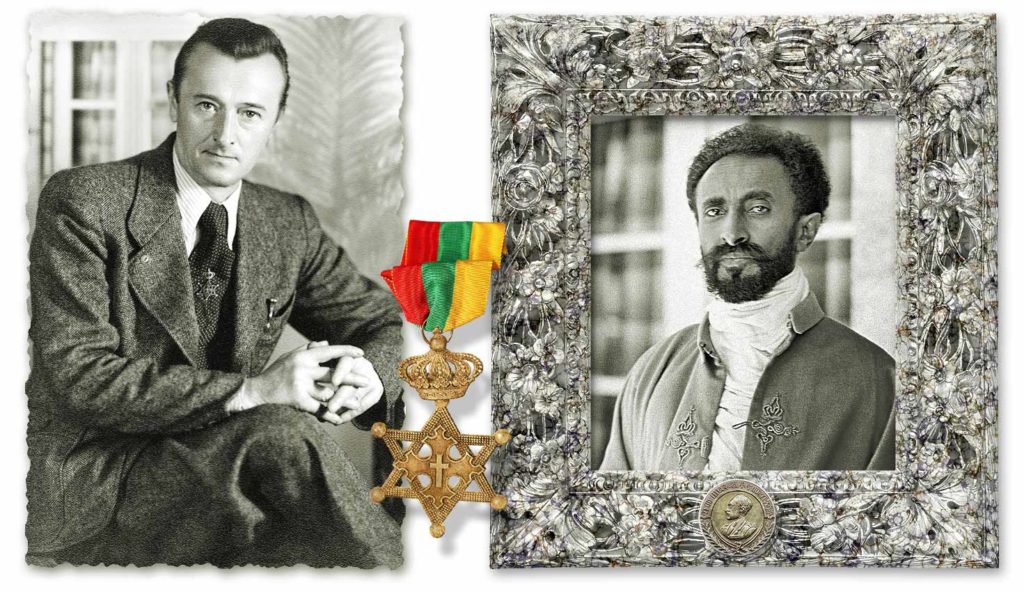

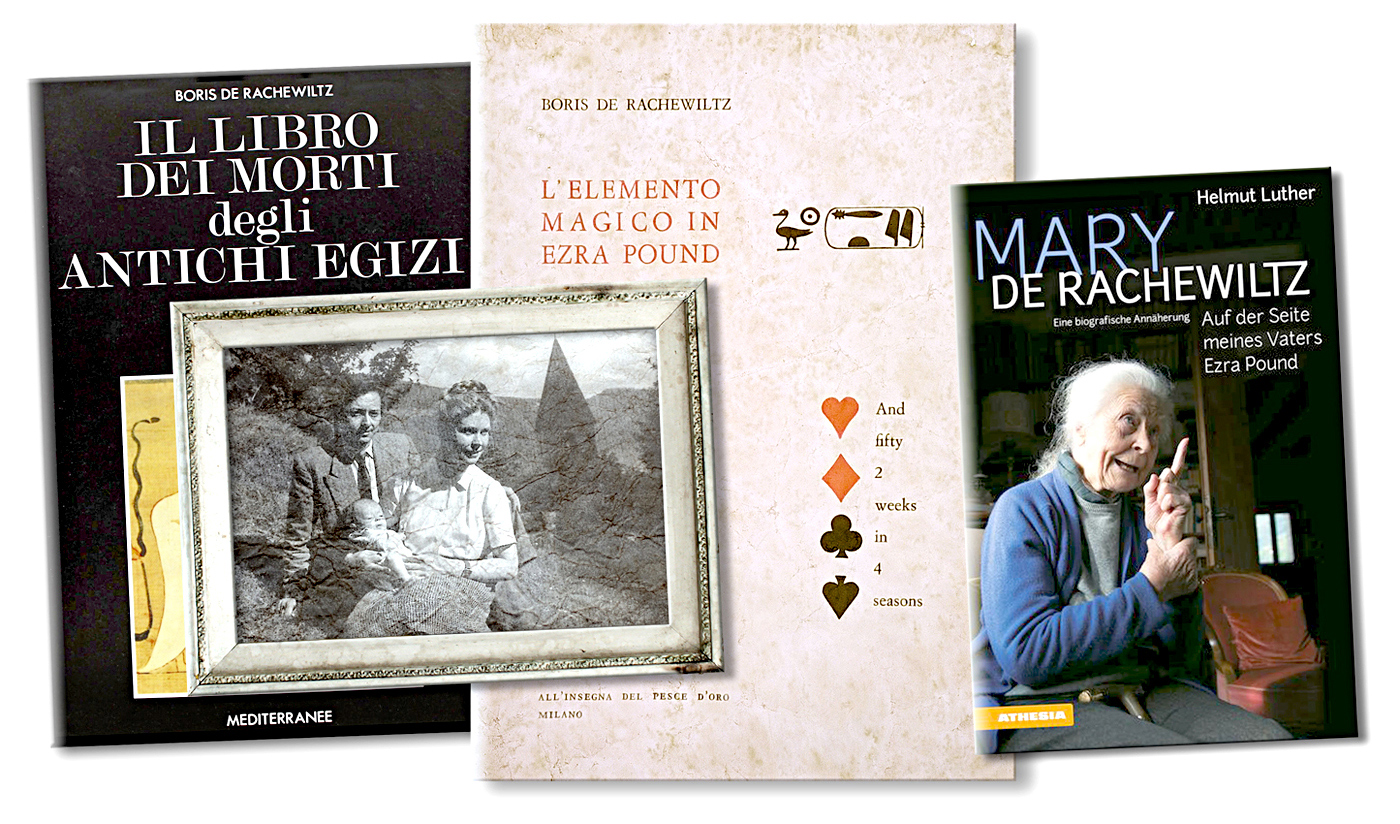

Mary de Rachewiltz 5), die Tochter Olga Rudges, merkte auf Grund ihrer Recherchen sehr bald, dass die Konstruktion der Stiftung nur ein Instrument war, mit dem sie von Jane Rylands um das Erbe ihrer Mutter gebracht werden sollte. In ihrer Verzweiflung suchte sie in Venedig damals Hilfe, unter anderem bei meiner geschätzten Künstlerfreundin Liselotte Hohs, die schon zu Lebzeiten ihres verstorbenen Mannes, des Anwalts Giorgio Manera 6), mit Olga und Ezra Pound eine intensive Freundschaft verband. Liselotte Hohs, als unmittelbare Zeitzeugin, bestätigte mir einige Informationen, die ich in vielen Interviews mit testimoni contemporanei veneziani in den letzten Jahren erfahren und notiert hatte, u. a. von Drohungen und anonymen telefonischen Einschüchterungsversuchen von amerikanischer Seite, falls weiterhin versucht werden sollte, sich mit Gründungsdetails der Ezra Pound Stiftung und dem Ehepaar Rylands zu befassen. Hier ist anzumerken, daß Jane Rylands nach dem Eintreffen in Venedig den gemeinsamen Lebensunterhalt als Lehrerin 7) am Luftwaffenstützpunkt Aviano verdiente, während ihr Mann an seiner Dissertation arbeitete. Sie hatte also sehr gute Kontakte zu amerikanischen Offizieren am Aeroporto militare di Aviano “Pagliano e Gori”, der sogenannten Aviano Air Base, der von der US-Luftwaffe als Standort des 31st Fighter Wing benü̈tzt wird. „Philip was still writing his dissertation, which would take him the better part of twelve years to finish. Meanwhile Jane supported both of them by teaching at the American air base in Aviano, an hour north of Venice.“ 8) 9)

Auch Marys Ehemann, Boris de Rachewiltz10), bekannter italienischer Ägyptologe, wollte Olga Rudge helfen und begann, Einzelheiten dieser zweifelhaften Vorgänge an die Öffentlichkeit zu tragen. Als er einen Prozess gegen die Rylands vorbereitete, wurde er bei Forschungsarbeiten in Ägypten unter dem Vorwurf des Waffenschmuggels überraschend von der CIA festgenommen und kam nur unter größten Schwierigkeiten frei. Er starb unerwartet am 3. Februar 1997 in Dorf Tirol bei Meran.11) Über eine Vergiftung wird hinter vorgehaltener Hand gesprochen – eine Obduktion des Leichnams wurde niemals durchgeführt.

Über die zweifelhafte Gründung der Ezra Pound Stiftung und also der Enteignung Olga Rudges durch Jane Rylands12) wurde in keiner italienischen Presse, ja nicht einmal in venezianischen Lokalblättern, jemals etwas berichtet. Ins Gerede kam Jane Rylands dennoch – nicht wegen des Betrugs an Olga Rudge, sondern aufgrund der zweifelhaften Dinge, die sich auftaten, als sie sich als Freundin Peggy Guggenheims einschmeichelte, sie aufopfernd bis in den Tod pflegte – und nach deren Ableben Rylands’ Ehemann, Philip, 1986 deputy director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, 2000 director und 2009 Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation for Italy wurde. In einer Buchbesprechung von John Berendts Buch The City of Falling Angels in der Denver Post geht Sandra Dallas besonders auf das Kapitel The Last Canto ein: „Venetians gossiped that Jane Rylands and her husband, who took care of Peggy Guggenheim in her last days, had a habit of making themselves indispensable to elderly women, then getting their hands on the women’s assets, selective gerontophilia, one called it.“ 13) 14) 15)

Aber das ist ein anderer, überaus widerwärtiger Skandal, über den ich demnächst berichten werde.16)

1) „Olga Rudge Papers“, Yale Library, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

2) John Berendt, „The City of Falling Angels“, Penguin Press, New York, 2005.

3) „…There is his legendary mistress, once a celebrated violinist, later to decline into Alzheimer’s…“, Jan Morris, „Dirt in Venice“, The Guardian, London, September 24, 2005

Vgl. auch: „Olga Rudge, he asserts was cheated out of her property and Pound’s papers by two seemingly friendly expats one of whom was director of the Guggenheim museum, he then draws parallels between this and Henry James’ Aspen papers…“, Rotten Books, Tag Archives: John Berendt, April 21, 2012, https://rottenbooks.wordpress.com/tag/john-berendt/https://rottenbooks.wordpress.com/tag/john-berendt/

4) Sandra Dallas, „Venice secrets come to life“, Denver Post, September 22, 2005.

5) Mary de Rachewiltz, „Il rapporto Pound-Venezia“, „Ezra Pound a Venezia“, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Isola di S. Giorgio Maggiore, Venezia.

6) Giorgio Manera, „livelli di Venezia“, Ezra Pound a Venezia, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Isola di S. Giorgio Maggiore, Venezia.

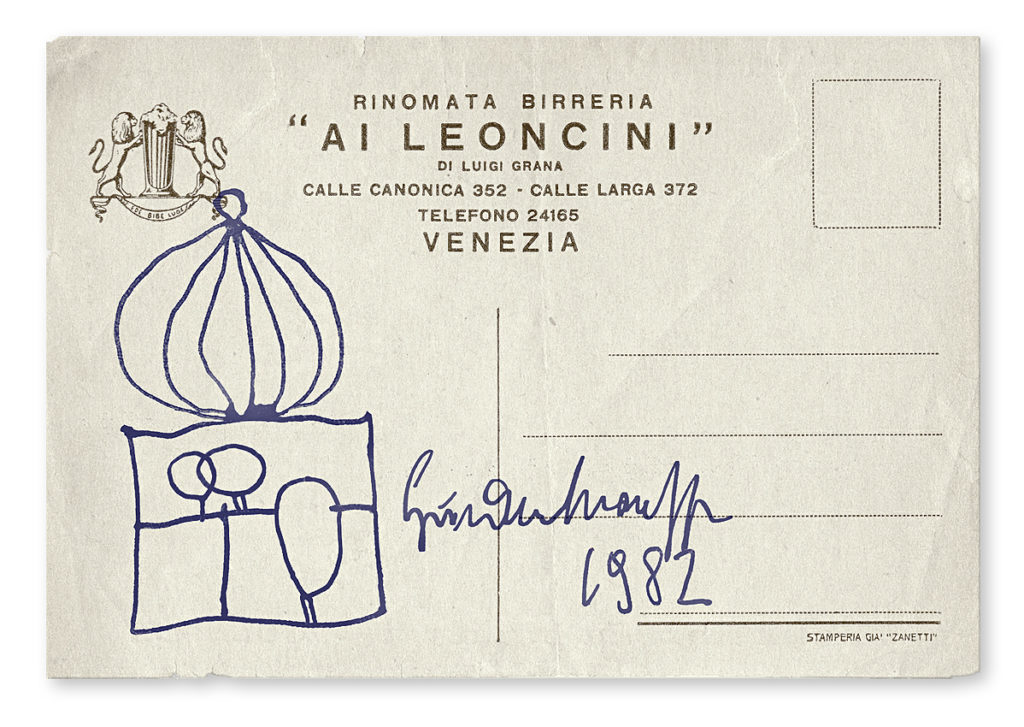

Vgl. auch: „Wagner in Italia“, a cura di Giorgio Manera a Giuseppe Pugliese, Marsilio, Venezia, 1982. (Con cronologia delle opere rappresentante in Italia dal 1871 al 1982.)

Giorgio Manera, „Wagner: cent’anni dopo“, Parole e musica, L’esperienza wagneriana nella cultura fra romanticismo e decadentismo, ondazione Giorgio Cini, Isola di S. Giorgio Maggiore, Venezia.

Giorgio Manera, „Libertà di stampa e dissidio morale“, Pan Editrice, Timone n.66, Milano 1977.

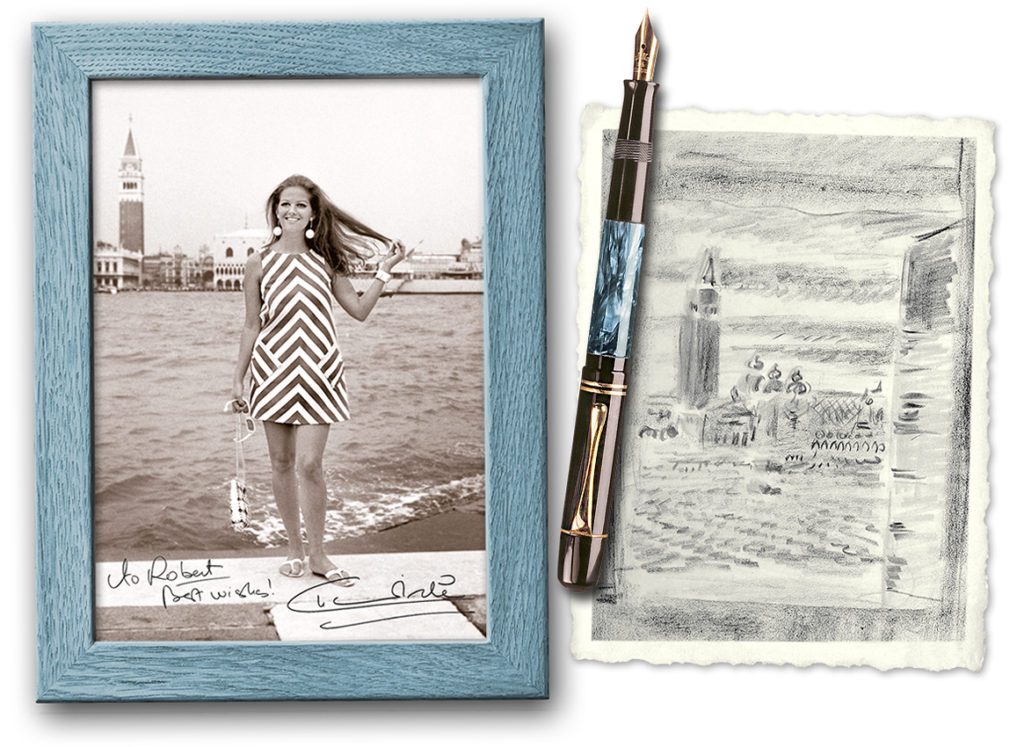

Manuela Pivato, „La contessa dell’anno“, La Nuova di Venezia e Mestre, 8 febbraio 2004. https://ricerca.gelocal.it/nuovavenezia/archivio/nuovavenezia/2004/02/08/VA3VM_VA301.html

7) Aviano American High School (also referred to as Aviano Middle/High School) is a European Department of Defense Education Activity secondary school located on the Italian owned NATO Air Base in Aviano.

8) John Berendt, „The City of Falling Angels“, Penguin Press, New York, 2005.

9) Aviano wurde und wird nicht nur als Zwischenlandesstation von CIA-Agenten für Aufklärungs-, Arbeits- und Entführungsflüge innerhalb Europas genützt, sondern dient ihnen auch als Headquater in Norditalien. (Siehe: „CIA Gefangenenflug Aviano-Ramstein-Kairo – Italiens Justiz rechnet mit CIA-Kidnappern ab.“ „Zumindest über einen Gefangenenflug gibt es jede Menge Details. Es handelt sich um einen CIA-Entführungsflug mit der Route Aviano- Ramstein-Kairo am 17. Februar 2003. Ein Flug, der gerade in Italien Bestandteil eines aufsehen erregenden Strafprozess gewesen ist. Heute wurde das Urteil gesprochen. 23 CIA-Agenten wurden, teils zu mehrjährigen Haftstrafen, verurteilt.“, 4.11.2009, interpool-tv, http://www.interpool.tv/politik/113-cia-gefangenenflug-aviano-ramstein-kairo.html

„CIA führte italienische Behörden in die Irre“, Der Standard, Wien, 7.12.2005.

10) Boris de Rachewiltz (Boris Luciano de Rachewiltz degli Arodis), (12. Februar 1926, Rom; † 3. Februar 1997, Dorf Tirol) wurde als Sohn eines italienischen Vaters und einer Mutter mit russischen Wurzeln in Rom geboren. Sein jüngerer Bruder war der spätere Mongolist und Sinologe Igor de Rachewiltz. Er heiratete 1946 Mary, die Tochter des amerikanischen Dichters Ezra Pound und der Musikerin Olga Rudge, und erwarb mit ihr in der Folge die Brunnenburg in Südtirol. De Rachewiltz studierte von 1951 bis 1955 am Pontificio Istituto Biblico und von 1955 bis 1957 an der Universität Kairo Ägyptologie. Der italienisch-russische Fürst war Assistent von Professor Ludwig Keimer am UNESCO-Dokumentationszentrum und setzte nach dessen Tod seine vergleichende Methode zwischen Archäologie und Ethnologie fort, indem er 1969 die Ludwig Keimer Stiftung in Basel gründete. Im selben Jahr wurde er zum Professor für Orientalische Archäologie an der Universität von Jordanien ernannt. Nach diversen archäologischen und ethnographischen Feldforschungen im Nahen Osten, in Oberägypten und im Sudan unterrichtete er als Professor an der Pontificia Università Urbaniana.

11) Schon in den 50er-Jahren engagierte sich Boris de Rachewiltz für die Rehabilitierung Ezra Pounds, der wegen Unterstellungen, seine Bewunderung für den italienischen Faschismus kundgetan zu haben, isoliert und als Ausgestoßener behandelt wurde.

Vgl. auch: Tony Tremblay, „Boris is very intelligent and simpatico and interested in worthwhile things: The association and correspondence of Ezra Pound and Prince Boris de Rachewiltz.“ Paideuma, Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Spring 1999). https://www.jstor.org/stable/24726874

12) Elisabetta Povoledo, „Venice Bristles at the Savannah Treatment“, The New York Times, February 15, 2006. „Much less amused is Jane Rylands, a writer who is married to Philip Rylands, the director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection here. In the book, she is cast as an ambitious social climber who persuaded Olga Rudge, the then 90-something-yearold former mistress of Ezra Pound, to set up a foundation in honor of Pound that excluded Rudge’s immediate family. The foundation was eventually dissolved, in 1990, and Pound’s papers are now at Yale University.“

13) Sandra Dallas, „Venice secrets come to life“, Denver Post, September 22, 2005.

14) „That brings us back to Venice and the contemporary American couple who ingratiate themselves into the home of Peggy Guggenheim shortly before her death, then attach themselves to Olga Rudge, the elderly mistress of the poet Ezra Pound. The couple appear to cheat Rudge’s daughter out of her father’s letters and almost take the poet’s house.“ Alister McMillan, South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, October 16, 2005.

15) vgl.auch: Ted Wojtasik, „Serendipity in the City of Falling Angels“, 234 online journal of nonfiction writing that deserves to be read. June 28, 2011.

Michael Posner, „Plumbing the depths of Venice“, The Globe and Mail, Toronto, Canada, November 1, 2005.

„Behind the scenes at the Venice museum“, The Times, London, November 19, 2005.

David Thomson, „A Book To Carry You Away – Berendt Does Venice, Loosely“, Observer, New York, March 10, 2005.

Adam Goodheart, „The City of Falling Angels: There’s Life After Lady Chablis“, The New York Times, New York, September 25, 2005.

„Sink and swim“, The Economist, New York, September 24, 2005.

Hanne Borchmeyer, „Das amerikanische Künstlermilieu in Venedig: Von 1880 bis zur Gegenwart“, STUDI – Schriftenreihe des Deutschen Studienzentrums in Venedig, Band 10, Akademie Verlag, 2013.

Luciano Mangiafico, „Attainted: The Life and Afterlife of Ezra Pound in Italy“, Open Letters Monthly, August 31,2012, https://www.openlettersmonthlyarchive.com/olm/attainted-the-lifeand-afterlife-of-ezra-pound-in-italy

Cat Bauer, „All Saints Day 2014 on the Island of San Michele, Venice“, Venetian Cat – The Venice Blog, November 9, 2014, https://venetiancat.blogspot.com/search?q=Olga+Rudge

16) Henri Neuendorf, „Philip Rylands to Resign From the Peggy Guggenheim Collection After 35 Years“, Art World, December 12, 2016.

Alastair Smart, „Philip Rylands: Guardian of a Guggenheim Legacy“, Impressionist & Modern Art, May 3, 2017

„Philip Rylands – Director, Emeritus of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and Foundation Director for Italy“, Guggenheim Staff, New York, June 21, 2021.

Milton Esterow, „The Bitter Legal Battle over Peggy Guggenheim’s Blockbuster Art Collection“, Vanity Fair, January 5, 2017

Other sources

Anne Conover, “Olga Rudge und Ezra Pound“ Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2001.

M. E. Grenander, Book Review: „The Roots of Treason: Ezra Pound and the Secret of St. Elizabeth’s“ by E. Fuller Torrey. McGraw Hill Book Company, New York; 1984.

Omar Pound & Robert Spoo, “Ezra and Dorothy Pound: Letters in Captivity“. Oxford University Press, New York, 1999.

Belinda McKeon, “Getting down to the grain“, Interview with John Berendt, author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil on the eve of the release of his long-awaited new book, „The City of Falling Angels“. The Irish Times, Dublin/New York, September 24, 2005.

James Urquhart, “Gossip merchant“. Financial Times, London, September 30, 2005.

Jonathan Keates, “Paddling in murky waters“, The Spectator, London, 2005. („…Lift the stones of Venice, the book implies, and we shall discover life forms quite unknown to Ruskin wriggling beneath them. One such, according to Berendt, is Jane Rylands, wife of the director of the Peggy Guggenheim collection and fingered here for trying to scoop up Ezra Pound’s papers in the name of a foundation established with the blessing of his mistress Olga Rudge. Shabby as her behaviour is made to seem, Berendt’s animus against Mrs Rylands, portrayed as a gold-digging harpy from the wrong side of the tracks, is virulent enough for us to hope that she has secured the services of a competent lawyer.“)

Raleigh Trevelyan, “Fire on Water“, The Wall Street Journal. New York, September 24, 2005.

Andrea Visconti, “I molti misteri della Fenice“, La Nuova di Venezia e Mestre, 21.10.2005.

Alexander Kluy, “Der Venedig-Effekt“. Der Standard, Wien, 11./12.08.2007.

Georg Kohler, “Das Paradies verlieren – und finden“. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 07.08.2015.

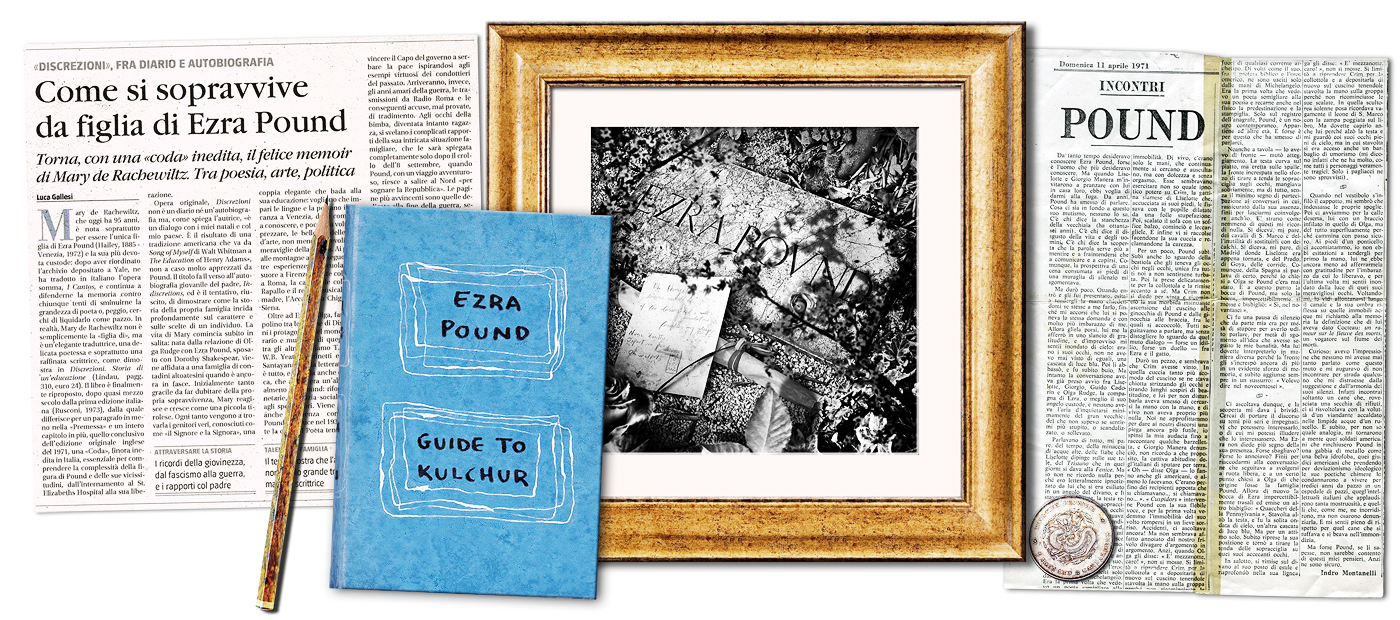

Luca Gallesi, “Come si sopravvive da figlia di Ezra Pound – Torna, con una «coda» inedita, ilfelice memoir di Mary de Rachewiltz Trapoesia, arte, politica“. il Giornale, 16.03.2021.

J.J. Wilhelm, “Ezra Pound – The Tragic Years 1925-1972“. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State UP, 1994.

Viorica Patea, “Patrizia de Rachewiltz’s My Taishan: Confessions in the Pound Tradition“*. Universidad de Salamanca, Spain. *This study is part of a research project funded by the Regional Ministry of Culture of the Regional Autonomous Government of Castile & Leon (ref. number SA342U14).

Patrizia de Rachewiltz, “My Taishan“. Raffaelli Editore, Rimini, 2007.

Albert Willeit, Annemarie Laner, “Ein Rendezvous mit Ezra Pound“. Gemeinde Gais, 15.10.2010.

Mark Byron, Sophia Barnes, “Ezra Pound’s and Olga Rudge’s The Blue Spill: A Manuscript Critical Edition“. Bloomsbury, London, 2019.

Robin Saikia, “Olga Rudge – Ezra Pound: birdsong and Vivaldi“. Ezra Pound and Vivaldi, .

The Rudge Collection, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Institute of Music, Island of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice.

Stefanie Bisping, „Pflanzt Bäume – Südtirol. In der Brunnenburg fand der Dichter Ezra Pound nach zwölf Jahren in einer psychiatrischen Anstalt 1958 eine neue Heimat. Sein Enkel leitet hier eine Gedächtnisstätte.“ Die Presse, 31.12.2021.

Mauro Piccinini, “Percussive Music for a Triangle: Ezra Pound’s Relationship with George Antheil and Olga Rudge“. 24.12.2018. academia.edu

Yolanda Morató, “Modernist Music and Avant-garde Identity in England“. Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla.

Massimo Bacigalupo ed., “Ezra Pound, Posthumous Cantos.“ Fyfiel Books, Carcanet Press, Manchester 2015.

Terrence Hobin, “Olga Rudge“. Thats what i’d like to know. https://thatswhatidliketoknow.wordpress.com/2016/05/03/exiles-ezra-pound-bobby-fischer/olgarudge/

Patrick McGuinness: “Ezra Pound: Posthumous Cantos edited by Massimo Bacigalupo review – fresh insights into an epic masterpiece“. The Guardian, London, November 27, 2015.

Robert McCrum: “The Bughouse: The Poetry, Politics and Madness of Ezra Pound – review“. The Guardian, London, February 20, 2017.

Mark Ford: “The Bughouse by Daniel Swift review – Ezra Pound, antisemitic and in the asylum – Pound’s arraignment for treason and spell in a psychiatric hospital is a great subject, so why write such an annoying book?“. The Guardian, London, March 9, 2017.

The Allen Ginsberg Project, “Ezra Pound“. October 30, 2018. https://allenginsberg.org/2018/10/t-o-30/

Frederic Morel, “Ezra Pound: The Rise and Fall of the London Vortex – From the Perspective of Pierre Bourdieu’s Field of Cultural Production“. Scriptie ingediend tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de Taal-en Letterkunde: Engels. Universiteit Gent, Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Vakgroep Engelse Literatur, Academiejaar 2007-2008.

John Gery, Daniel Kempton, H.R. Stoneback: “Ezra Pound, T. E. Hulme, Edward Storer: Imagism as Anti-Romanticism in the Pre-Des Imagistes Era“. The University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, 2013.

Sergey Zenkevich, “’Ia pochuial buriu‘. Mikhail Zenkevich as Ezra Pound’s Translator“. Russian State University for the Humanities, Moscow, 2001.

Margaret Fisher, “The Transparency of Ezra Pound’s Great Bass“. Review by Roxana Preda. The Ezra Pound Society, 2014, Kindle 2013.

Ian Probstein, “The River of Time: Time-Space, Language and History in Avant-Garde, Modernist, and Contemporary Poetry“. Academic Studies Press, Boston, 2017.

G. Singh, Antonio Pantano, “La musa di Ezra Pound – Olga Rudge“. Edizioni dell’ape, Milano, 1994.

Jan Küveler, “Ezra Pound, Porträt eines begnadeten Antisemiten“. Welt, Berlin, 29.01.2020.

Catherine E. Paul, “Fascist Directive: Ezra Pound and Italian Cultural Nationalism“. Liverpool Scholarship Online, Liverpool, 2017.

Ira B. Nadel, “The Cambridge Introduction to Ezra Pound“. Cambridge Introductions to Literature, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 2007.

Massimo Bacigalupo, “Ezra Pound, Italy, and the Cantos“. Clemson University Press: The Ezra Pound Center for Literature Book Series, 4; Liverpool, 2020.

Hugh Kenner, “The Poetry of Ezra Pound“. University of Nebraska Press; Reprint Edition, Nebraska, 1985. (This pioneering study did much to rehabilitate Ezra Pound’s reputation after a long period of critical hostility and neglect. Published in 1951, it was the first comprehensive examination of the Cantos and other major works that would strongly influence the course of contemporary poetry.)

Joshua Kotin, “The Cantos of Ezra Pound CX-CXVI“. The Fuck You Press. New York, 1967.

Andrés Claro, “Ezra Pound’s Poetics of Translation – principles, performances, implications“. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Wolfson College, University of Oxford, Oxford, 2004.

Mark Byron, “In a Station of the Cantos: Ezra Pound’s ‘Seven Lakes’ Canto and the Shō-Shō Hakkei Tekagami“. Literature & Aesthetics 22, Sydney, 2012.

Mark Byron, “Ezra Pound’s Eriugena“. Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2014.

Mark Byron, “Textual criticism“. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010.

Mark Byron, “Ezra Pound in Context“. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010.

Michael Kindellan, “Ezra Pound, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and philology“. Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Universität Bayreuth, Bayreuth.

Massimo Bacigalupo, “Tigullio Itineraries : Ezra Pound and Friends“. Università degli studi di Genova, Genova, 2008.

Roxana Preda, “Constantin Brâncuşi Vorticist: sculpture, art criticism, poetry“. academia.edu, 2013.

Sean Pryor, “Particularly Dangerous Feats: The Difficult Reader of the Difficult Late Cantos“. academia.edu, 2009.

Special issues by and about Ezra Pound by date of publication

Ezra Pound, “Personae“. Elkin Mathews, London 1909 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Exultations“. Elkin Mathews, London, 1909 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Provenca“. Small, Maynard and Company, Boston, 1910 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “The Spirit of Romance“. Small, J. M. Dent and sons, London, 1910 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Canzoni“. Elkin Mathews, London, 1911 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Ripostes“. Stephan Swift and Co, London, 1912 [First edition, first issue. 64 pp.].

Gaudier-Brzeska/Ezra Pound, “A Memoir by Ezra Pound including the published writings of the sculptor, and a selection from his letters“. John Lane, London, 1916 [First edition].

Thomas Stearns Eliot, “Ezra Pound, his metric and poetry“. A. A. Knopf, New York, 1917 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Umbra“. Elkin Mathews, London 1920 [First edition].

Remy de Gourmont, “The Natural Philosophy of Love“. Translated and with a Postscript by Ezra Pound. Boni and Liveright, New York, 1922 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Antheil and the Treatise of Harmony with Supplementary Notes“. Pascal Covici, Publisher, Inc., Chicago, 1927 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Selected Poems“. Edited by T. S. Eliot. Faber & Gwyer, London, 1928 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Hark the Herald“. The Hours Press, Paris, 1928 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Ta Hio – The Great Learning“. University of Washington, Chapbooks no. 14, Washington, 1928 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Imaginary Letters“. Black Sun Press, Paris, 1930 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “A Draft of XXX Cantos“. Paris Hours Press, 1930 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Homage to Sextus Propertius“. Faber & Faber, London, 1934 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Jefferson and/or Mussolini“. Stanley Nott Ltd, London, 1935 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Make it New“. Yale University Press, Yale, 1935 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Introductory Text Book“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York (Rapallo), 1938 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “What Is Money For? A Sane Man’s Guide to Economics“. Greater Britain Publications, London, 1939 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “A Selection of Poems“. Faber & Faber, London, 1940 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “The Pisan Cantos“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1948 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “If This Be Treason“. Printed for Olga Rudge by Tipografia Nuova, Siena, 1948 [First edition].

Charles Norman, “The Case of Ezra Pound“. The Bodley Press, New York, 1948 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Personae – The Collected Poems of Ezra Pound“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1949 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Confucius: The Unwobbling Pivot/The Great Digest/The Analects“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1951 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Guide to Kulchur“. New Directions Pub. Corp., Norfolk, Connecticut, 1952.

Ezra Pound, “The Translations of Ezra Pound“. Faber & Faber, London, 1953.

Ezra Pound, “Section: Rock-Drill 85-95 de los Cantares“. Faber & Faber, London, 1957.

Ezra Pound, “Dyptych Rome – London. Homage to Sextus Propertius & Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, Contact and Life“. Mardersteig, Verona, 1957 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Cantos et poèmes choisis“. Texte et traduction. Pierre Jean Oswald, Paris, 1958.

Ezra Pound, “Pavannes and Divagations“. Peter Owen Limited, London, 1960.

Ezra Pound, “Cavalcanti Poems“. Officina Bodoni, Verona, 1966 [Limited Edition].

Ezra Pound, “Canto 90“. Serie ‚Il quadrato‘ Nr. 23, Verona, 1966 [Limited edition of 1000 copies].

Ezra Pound, “The Caged Panther: Ezra Pound at St. Elizabeths“. Twayne Publishers, New York, 1967 [First edition].

Ezra Pound/James Joyce, “The letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce, with Pound’s essays on Joyce“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1967.

Ezra Pound, “Drafts & Fragments of Cantos CX-CXVII“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1968 [First edition].

Thomas Stearns Eliot, “The Waste Land“. Facsimile Manuscript of T S Eliot’s The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound’s annotations. Faber & Faber, London, 1971 [First edition].

Giuseppe Santomaso/Ezra Pound, “An Angle“. Erker Galerie, St. Gallen/Switzerland, 1972 [Deluxe Edition with Original Lithographs. Signed by the Author and the Artist].

Ezra Pound, “A Memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York. 1974 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Radio Speeches of World War II“. Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. 1978.

Ezra Pound, “Personae & a draft of XXX Cantos“. Franklin Center/Franklin Library, Pennsylvania, 1981 [First edition/Limited Edition].

Ezra Pound, “From Syria: The worksheets, Proofs, and Text“. Copper Canyon Press, Port Townsend, WA, 1981 [First Separate Edition].

Ezra Pound/Wyndham Lewis, “The letters of Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1985 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Opere Scelte (I Meridiani)“. Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milan, 1985 [First edition].

Ezra Pound/Louis Zukofsky, “Pound/Zukofsky – Selected letters of Ezra Pound and Louis Zukofsky“. New Directions Pub. Corp., New York, 1987 [First edition].

Ezra Pound/Rudd Fleming, “Sophocles Elektra: a Version By Ezra Pound and Rudd Fleming“. Faber and Faber, London, 1990 [First edition].

René Crevel/Ezra Pound, “A nation which does not feed its best writers is a mere barbarian dung-heap“. Éditions Rosbif. Paris, 1992 [First edition, slipcased copie on white Moulin-de-Gué paper, signed by Pound’s daughter and translator, Mary de Rachewiltz, have an extra signed bonus colour etching].

Leon Surette, “The Birth of Modernism: Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, and the Occult“. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 1993 [First edition]. (While W.B. Yeats‘ occultism has long been acknowledged, Surette is the first to show that Ezra Pound’s early intimacy with Yeats was based largely on a shared interest in the occult, and that Pound’s The Cantos is a deeply occult work. Surette argues that Pound’s editing of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land was not motivated primarily by stylistic concerns, as has generally been contended by the New Critics, but by thematic considerations. In fact, it was precisely because Eliot knew Pound to be well informed about the occult that he asked for Pound’s assistance with The Waste Land.)

Paul Morrison, “The Poetics of Fascism: Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Paul de Man“. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1996 [First edition].

Mary de Rachewiltz, “Ezra Pound, Father And Teacher: Discretions“. New Directions Pub. Corp., Norfolk, Connecticut, 2005 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Le Testament“. Second Evening Art Publishing. The definitive manuscript for Ezra Pound’s first opera in facsimile, 110 color plates. Emeryville CA, 2011 [Limited facsimile edition with audio CD].

W.B. Yeats, “Ezra Pound, and the Poetry of Paradise“. Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group), London, 2018 [First edition].

Alessandro Rivali, “Ho cercato di scrivere paradiso. Ezra Pound nelle parole della figlia: conversazioni con Mary de Rachewiltz cercato di scrivere Paradiso“. Mondadori, Milan, 2018 [First edition].

Ezra Pound, “Cathay“. Edited by Timothy Billings. Introduction by Christopher Bush. Foreword by Haun Saussy. Fordham University Press, New York, 2020.

Magazines and Periodicals by date of publication

Blast – Review of the Great English Vortex, No. 2. Edited by Wyndham Lewis. Elkin Mathews, Publisher, London, 1915.

The Dial. Volume LXXIII, No. 5. Art and literary magazine. Edited by Margaret Fuller and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Boston and Concord, 1922.

This quarter. No. 2. Edited by Ernest Walsh and Ethel Moorhead. Milan, 1925.

The Exile, No. 3. Edited by Ezra Pound. Pascal Covici, Publisher, Chicago, 1928.

The New Review. An International Notebook for the Arts, published from Paris. Edited by Samuel Putnam. Paris, 1931.

The Paris Review, No. 28. “Ezra Pound, The Art of Poetry“. Interviewed by Donald Hall. Big Sandy, Texas, 1962.

Fanatic, No. 2. Special Low Mindedness Issue. Edited by William Levy. Includes “Sassoon“ by Ezra Pound. Amsterdam, 1976.

Partisan Review, Vol. XLIV, No. 1. Peter Shaw, „Ezra Pound on American History“. New York, 1977.

Artforum International Magazine, Volume 16, No. 3. Brice Rhyne, “Henri Gaudier-Brzeska: The Process of Discovery“. New York, 1978.

Unmuzzled OX Volume XII, No. 2. Edited by Michael Andre. The Cantos (125-143) by Ezra Pound. New York, 1986. (Unmuzzled OX was a quarterly of poetry, art and politics founded in 1971 by poet Michael Andre, edited in New York City and Kingston, Ontario.)

Paideuma – Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics, No. 10.3. Edited by Ben Friedlander. Orono, Maine, 2009. https://paideuma.wordpress.com/

I am very interested in further reports from contemporary witnesses.

I kindly ask you to contact me at graphics@sackl-kahr.com

Sono molto interessato a ulteriori rapporti di testimoni contemporanei.

Vi chiedo gentilmente di contattarmi all’indirizzo graphics@sackl-kahr.com

Latest message

THE EZRA POUND CENTER FOR LITERATURE

May 30 – June 25, 2022

The University of New Orleans is pleased to offer the rare opportunity to take Poetry-Writing Workshops and seminars on The Poetry of Ezra Pound. The program is held at Brunnenburg, the northern Italian castle that served as Pound’s residence during his later years and is currently the home of his daughter, Mary de Rachewiltz, and her son, Dr. Siegfried de Rachewiltz.